I came upon the word transmissions while thinking about how the ethereal, corporeal, and technical dimensions of ballet resonate in the artworks and souvenirs it produces. Transmissions are subject to interference and interruption. Ballets are conveyed to us through mediations, anecdotes, and bodies. And often when I’m watching ballet in its contemporary manifestations, I wonder how these transmissions have occurred.

I started looking into the history of ballet in the twentieth century… Through a web of genealogies, I eventually arrived at the flamboyant intersection of ballet and art in New York, beginning in the 1930s. There the avant-garde experiments of the previous decades in Europe incited a particularly intense cross-contamination, an overt articulation of homosexual erotics long before the emergence of a public language around queerness. Looking at modern American art of this period through the prism of ballet reveals a tangle of interrelationships, collaborations, derivations, and hybrid aesthetic programs that still feel surprisingly contemporary. — Nick Mauss*

Two years after the close of TRANSMISSIONS—Nick Mauss’ multimedia installation at the Whitney Museum of American Art—the museum and Dancing Foxes Press have published an exhibition catalog that beautifully extends the show, combining performance and exhibition images from the Whitney with an extensive selection of new illustrative and textual documentation.

Essays by Mauss, Joshua Lubin-Levy, and exhibition organizers Scott Rothkopf, Elisabeth Sussman, and Allie Tepper—as well as a conversation between Mauss and the dancers who performed during the run of the show—round out this essential volume, a complement to and in dialog with recent catalogs by Jarrett Earnest (The Young and Evil—Queer Modernism in New York 1930–1955) and Samantha Friedman and Jodi Hauptman (Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern).

I drew multiple webs of interrelationships, elective affinities, and echo waves of influence, focusing as much on the social, professional, sexual, and collaborative points of contact as on transhistorical resonances that were in some cases perhaps fantasy—eschewing standard mappings of modern art… [embracing] anachrony and distortion over apparent objectivity…

My decision to insist on ballet as the fulcrum in TRANSMISSIONS was also a response to the ubiquity of postmodern dance derivations within the contemporary museum environment and the reductive version of modernity that these prequalified dance idioms signify and cement. Contemporaneity is reduced to a “look” of modernity. Modernist ballets make for engaging historical documents precisely because their own relationship to history is a kind of suspension of disbelief; they are intrinsically modernist, even if they don’t “signal” modernity to contemporary eyes.— Nick Mauss*

The world of the spectator, the receiver, was a primary lens through which I constructed TRANSMISSIONS, and the flux of the exhibition’s daily audience over the course of two months took on a central role within it. This book is similarly directed at the wholly different—private, rather than social—negotiations of the reader. — Nick Mauss*

NICK MAUSS, TRANSMISSIONS (Brooklyn: Dancing Foxes Press; New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2020).

See Benedict Nguyen on performing in Transmissions.

Listen to Fran Lebowitz and Nick Mauss in conversation on the occasion of Transmissions at the Whitney, 2018.

*Nick Mauss text—from the catalog essay “Gesturing Personae” and TRANSMISSIONS jacket copy—courtesy and © the artist.

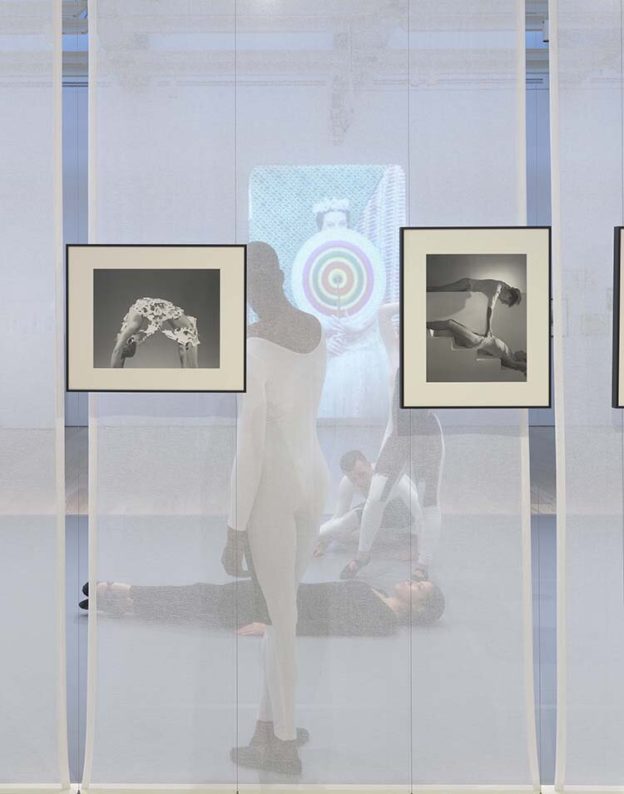

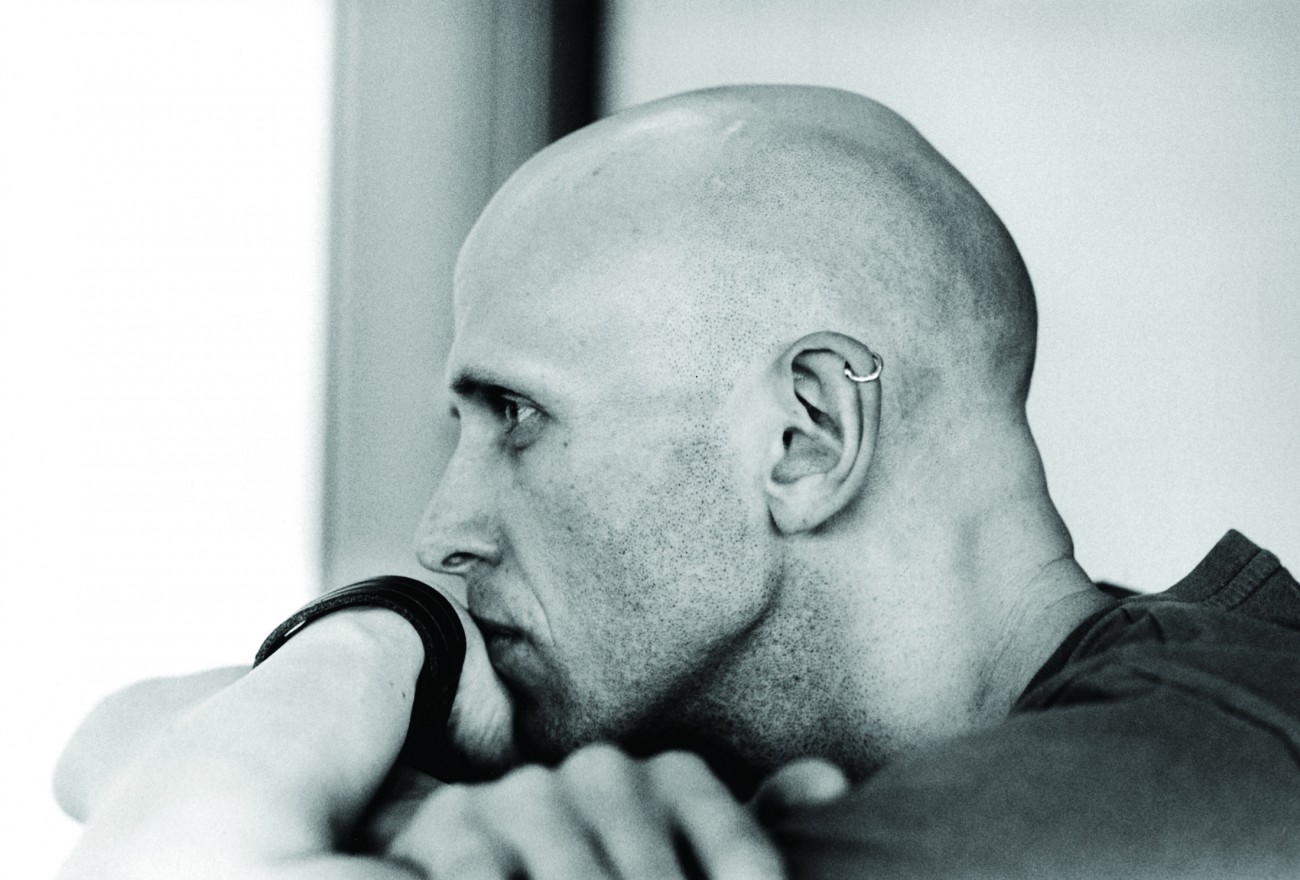

Nick Mauss, Transmissions, Whitney Museum of American Art, March 16, 2018–May 14, 2018; exhibition catalog, Whitney and Dancing Foxes Press, 2020, from top: installation view, Whitney, 2018, photograph by Ron Amstutz; Carl Van Vechten, Janet Collins in New Orleans Carnival, 1949, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts; George Platt Lynes, Tex Smutney, 1941, Kinsey Institute, Indiana University , Estate of George Platt Lynes; Transmissions performance photograph of Quenton Stuckey, March 13, 2018, by Paula Court, with Gaston Lachaise, Man Walking (Portrait of Lincoln Kirstein), 1933, at left; Dorothea Tanning, cover of Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo’s 1945–1946 program, Artists Rights Society, New York / ADAGP, Paris; installation view, Whitney, 2018, images on scrim, Lynes, Ralph McWilliams (dancer), 1952, Lynes, Tex Smutney, Carl Van Vechten slideshow on rear wall, dancers Brandon Collwes, Quenton Stuckey, and Kristina Bermudez, photograph by Amstutz; dancers Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams, and (seated) George Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky during rehearsals for Agon, 1957, choreographed by Balanchine for New York City Ballet, photograph by Martha Swope, Jerome Robbins Dance Division; Bermudez (left), Burr Johnson, Nick Mauss, and Fran Lebowitz, May 9, 2018, at the Whitney, photograph by Court; Pavel Tchelitchew, Portrait of Lincoln Kirstein, 1937, oil on canvas, collection of the School of American Ballet, courtesy Jerry L. Thompson; Louise Lawler, Marie + 90, 2010–2012, silver dye bleach print on aluminum, Whitney, courtesy and © the artist and Metro Pictures; (Mauss printed Lawler’s image of Marie, Edgar Degas’ Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, circa 1880, on the Transmissions dancers’ white leotards); Lynes photograph of Jean Cocteau, Bachelor magazine, April 1937; Transmissions performance photograph by Paula Court; Paul Cadmus, Reflection, 1944, egg tempera on composition board, Yale University Art Gallery, bequest of Donald Windham in memory of Sandy M. Campbell, courtesy and © 2019 Estate of Paul Cadmus, ARS, New York; Cecil Beaton, photograph of poet Charles Henri Ford in a costume designed by Salvador Dali, silver gelatin print, collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody; artworks by Pavel Tchelitchew, John Storrs, Elie Nadelman, Gustav Natorp, and Sturtevant, and photographs by Ilse Bing, arranged in front of Mauss’, Images in Mind, 2018, installation view, Whitney, 2018, photograph by Amstutz; Mauss’ re-creation of costume designed by Paul Cadmus for the 1937 ballet Filling Station (choreographed by Lew Christensen), fabricated by Andrea Solstad, 2018, and Nadelman, Dancing Figure, circa 1916–1918, installation view, Whitney, 2018, photograph by Amstutz; Man Ray, New York, 1917 / 1966, nickel-plated and painted bronze, Whitney;, courtesy and © Man Ray 2015 Trust, ARS, New York / ADAGP, Paris; Mauss and Lebowitz in conversation at the Whitney, 2018, photography courtesy and © Izzy Dow; Murals by Jared French exhibition brochure, Julien Levy Gallery, 1939; Transmissions performance photograph of Anna Thérèse Witenberg, March 13, 2018, by Court; Dorothea Tanning, Aux environs de Paris (Paris and Vicinity), 1962, oil on linen, Whitney Museum of American Art, gift of the Alexander Iolas Gallery; Maya Deren, The Very Eye of Night (1958, still), 16mm film, Anthology Film Archives, New York.