It’s great to be a provocateur. That’s what the world needs, this provocation. It stimulates thought and it stimulates ideas. It stimulates all kinds of conversations that don’t really have anything to do with the man himself. And who cares about the man himself? We’re looking at his art. — Charlotte Rampling

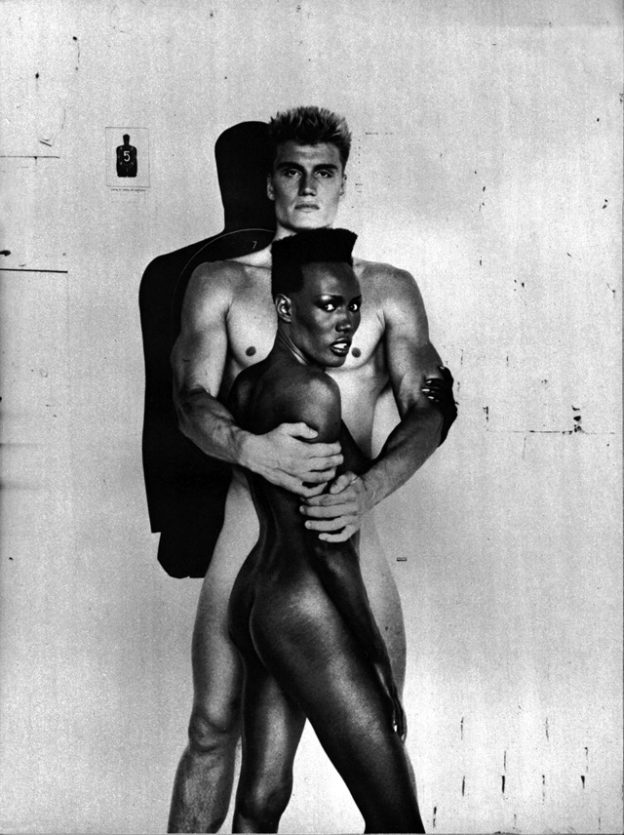

He was a little bit pervert, but so am I so it’s okay. — Grace Jones

I do consider myself a feminist, but I do consider the expression of machismo as an expression of a culture. Now, of course, Helmet wasn’t simply macho—it was more complicated than that—but he does look at a woman as a sexual object, and also an attraction and an anger toward her… It was actually extraordinary that Helmut was accepted by the industry because he was much more dangerous—much more ambiguous and frightening—than an Avedon or a Penn… Helmut photographed women the way Leni Riefenstahl photographed men. — Isabella Rossellini

Susan Sontag: As a woman, I find your photos very misogynist. For me it’s very unpleasant.

Bernard Pivot: You find him unpleasant?

Sontag: Yes. Not the man, the work… I never thought the man would look like the work. To the contrary. Even if you live through your work, you can be nice. I don’t expect a person to look like their work. Especially when it’s about fantasies and dreams.

Helmut Newton: I love women. There is nothing I love more.

Sontag: A lot of misogynist men say that. I am not impressed.

Newton: I swear—

Sontag: I’m sorry, I don’t think this is the truth. There’s an objective truth. The master adores his slave. The executioner loves his victim. A lot of misogynist men say they love women, but show them in a humiliating way.

Helmut actually loved strong women. — Nadja Auermann

When you’re 20 years old, 1.80 meters tall with blonde hair, you feel like a hunted deer. And Helmut Newton’s pictures made me stronger. I controlled the situation. I wasn’t the deer. I was equal to the hunter. I could decide what to do. I think a lot of people misunderstood that. — Sylvia Gobbel

I was very shy; I’d just turned 17. There was never a moment where I felt uncomfortable. I was just an amazing experience where I walked away saying, “This man is incredible.” He had a sort of twinkle in his eye—nothing serious, everything understated and very witty… Definitely, when I look at the pictures, it’s not me. It’s his imagination… I love the fact that I can be this different, through his lens.— Claudia Schiffer

I think he was Weimar. That’s how I think of him—connected to Brecht and Weill and George Grosz, that wonderful period of German Expressionism—that was Helmut. — Marianne Faithfull

Berlin for him was the very best of the Weimar Republic. Everything is possible, everything is allowed… What he liked about me was my guttersnipe style. I was not the usual elegant glamorous woman, but rather I had a portion of originality that comes from the lower classes of society. I suppose he also really like the eroticism of maids… It’s related to this Berlin period. — Hanna Schygulla

I loved my parents, they were great—very different influence on me. My mother was a very spoiled woman and quite hysterical in many ways, but pretty wonderful. And she encouraged me very much to become a photographer. My father was horrified by the idea. “You take pictures on the weekend for a hobby, my boy. You’ll end up in the gutter, my boy.” He was right, I did. But I had a good time in the gutter. — Helmut Newton*

The aesthetic of Helmut Newton—whose era is more distant from us now than the inspirational Weimar years were to Newton’s 1970s heyday—still provokes and intrigues, even in our less frivolous times.

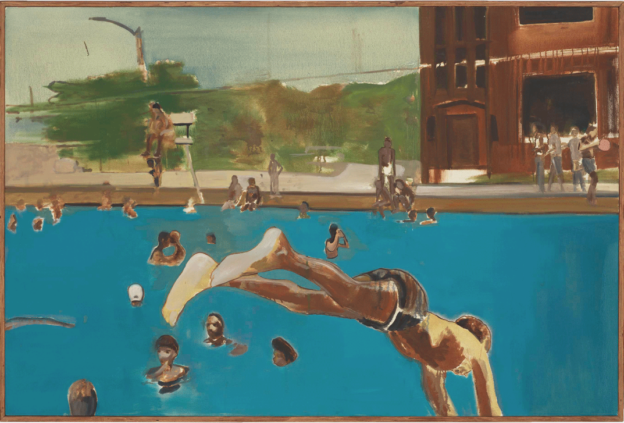

In the excellent new documentary feature HELMUT NEWTON—THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL—now streaming on Kino Lorber’s Kino Marquee—filmmaker Gero von Boehm captures the great photographer’s obsession with the female form pushed to the edge of submission or absolute triumph.

HELMUT NEWTON—THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL

Laemmle, Los Angeles.

Lumiere Cinema at the Music Hall, Los Angeles.

*Quotations and dialog from Gero von Boehm, Helmut Newton—The Bad and the Beautiful, courtesy of the filmmaker, Kino Lorber, and Nadja Auermann, Marianne Faithfull, Sylvia Gobbel, Grace Jones, Charlotte Rampling, Isabella Rossellini, Claudia Schiffer, and Hanna Schygulla. Susan Sontag segment originally from Apostrophes, 1979.

Helmut Newton, from top: Grace Jones and Dolph Lundgren, Los Angeles, 1985; Gero von Boehm, Helmut Newton—The Bad and the Beautiful (2020), still, Grace Jones; Grace Jones; Helmut Newton—The Bad and the Beautiful, still, Isabella Rossellini; David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini, Los Angeles, 1988; Faye Dunaway, 1987, Vanity Fair cover shoot; Charlotte Rampling, Arles, 1973; Paloma Picasso, St. Tropez, 1973; Elsa Peretti in Halston Bunny Costume, 1975; Newton in Berlin in the 1930s (2), shortly before leaving Germany; A Cure for a Black Eye, Jerry Hall, 1974; Alice Springs and Newton, Us and Them (Helmut and June Newton). Images courtesy and © the Helmut Newton Foundation, June Newton, Gero von Boehm, Lupa Film, and Kino Lorber.