STAIRWAY TO THE STARS—

THE LIVES OF PAUL R. WILLIAMS

By Barlo Perry

[In architecture,] bona fide vulnerability involves caring about the specific things you find and find out about so much that you will change your position to accommodate them: invulnerable architects see and learn things too, but they have a position, or a sense of mission, early arrived at, to which the learned and seen things contribute, without the power to change it.

— Charles W. Moore 1

Paul Revere Williams was born in Los Angeles in 1894 and was a resident of the city his entire life until his death in 1980. As the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects (inducted in 1923), Williams lived with his own unique set of formidable vulnerabilities. He would open his own firm at the age of 28 and within ten years would reach the first rank of residential architects in Los Angeles—signal achievements, given the time and place. Like many American cities in the first half of the twentieth-century, a system of by-laws and covenants in L.A. kept Black and white neighborhoods strictly segregated, and there were many districts—and country clubs—where Asians, Latinos, and Jews needn’t bother to apply. (Today, the laws have changed, but de facto segregation persists.)

Virtually everything pertaining to my professional life, during those early years, was influenced by my need to offset race prejudice.

— Paul R. Williams 2

After losing his mother and father to tuberculosis when he was young, Williams was encouraged by his foster parents and numerous mentors to pursue his interest in art and architecture, and he attended the local workshop of New York’s Beaux-Arts Institute of Design and the USC School of Engineering. This early advocacy enabled him to meet the challenges and, as he put it, “blank disapproval” of a society that had never seen, heard of, or could imagine a Black architect. Ultimately, Williams’ success was the result of a perfect marriage between the kind of man he was—dignified, elegant, methodical, adaptable, lightning-fast when developing concepts—and his artistic and professional aspirations: to please his clients by designing buildings of substance that would withstand the tests of time and trends.

The contiguous neighborhoods and municipalities strung along the Santa Monica Mountains north of Sunset Boulevard—Silver Lake, Los Feliz, the Hollywood Hills, Trousdale Estates, Beverly Hills, Holmby Hills, Bel Air, Brentwood, Pacific Palisades—have long been home to one of the world’s greatest concentrations of outstanding domestic design. The 1920s and 30s saw a dizzying array of styles and mutations spread across this expanse of hills and canyons, aeries and enclaves: Mission Revival, American Craftsman, Spanish Colonial Revival, East Coast Colonial, Monterey Revival (a blend of Mediterranean and old Williamsburg), French Norman, English Tudor, Georgian Revival. A glammed-up, neo-Classical/17th-century French/20th-century Art Deco amalgam was given the moniker “Hollywood Regency.” (Picture Jean Harlow’s bedroom in Dinner at Eight.) Cliff May was designing his first California ranch houses. And, here and there, outposts of an Adolf Loos-influenced Modernism began to appear.3 Williams, through study and practice, became a master of all of these forms. Perhaps the most important twenty-four hour period in his early career was the day (and night) in 1932 when, without food or sleep, he prepared the extensive drawings for a house that transportation magnate E. L. Cord proposed to build on his ten-acre Beverly Hills estate. The fact that Williams delivered the drawings the day after his initial meeting with Cord clinched the job. Cordhaven, the subsequent 32,000 sq. ft. mansion, defined the term showplace, and Williams, forever after, was on the map.

The Great Depression overlapped Hollywood’s Golden Age, but since the public never stopped going to the movies, stars—and their favored architects—were immune to the effects of the economic catastrophe. (To cite one example: Throughout most of the 1930s, Garbo’s weekly salary was four times greater than the average American worker’s annual salary.) During this period, over a hundred Williams-designed homes were built in the storied hills of Los Angeles, among them the residences of Tyrone Power, Lon Chaney, ZaSu Pitts, Virginia Bruce, Bryan Foy, Corinne Griffith, Nacio Herb Brown, Richard Arlen, Bert Lahr, Yip Harburg, and CBS founder William S. Paley. Needless to say, these houses were built in places Williams himself was barred from living in. (Two notable exceptions were the 1937 houses he designed for Black stars Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson in unrestricted areas .)

During the first twenty-five years of its existence, most of the work out of the Williams office was residential. However, a few important commercial projects came its way, and remain iconic. In 1938, Jules Stein asked Williams to design the Music Corporation of America Building—which has survived various name and ownership changes, and which still resembles a huge Georgian house dropped on the edge of downtown Beverly Hills. A consortium of show business executives and stars hired Williams and Gordon B. Kaufmann to design the Arrowhead Springs Hotel in the mountains east of Los Angeles (1939). Saks Fifth Avenue on Wilshire Boulevard is one of Williams’ most visible projects (1940 and 1948). And in the early 1940s he collaborated with Richard Neutra (among others) on the public housing project Pueblo del Rio in Vernon, and with Adrian Wilson on the Roosevelt Naval Base in Long Beach.

Obviously, Williams was hired for his great talent and facility. His clientele—the vast majority of whom were upper- and upper-middle-class whites—also knew that by hiring Williams, they were making a positive statement, however specific and circumscribed, about Black equality and access in the professional class. Nevertheless, Williams took steps to put his clients at ease which today seem extraordinary. He taught himself to draw upside-down, enabling him to sit across from (rather than next to) a potential client when bringing an idea to life. In a related precaution, he “often walked through construction sites with his hands behind his back so that no one would be put in the uncomfortable position of having to decide whether to shake his hand.”4

Shall We Go Modern ?

There is a question in the minds of many people as to what is meant by good modern architecture, and rightly so. They visualize the post-war house as a glittering machine, moored down to earth by wires and cement blocks, and they don’t want it. Good modern design is sensible, not tricky or gadgety. Construction materials will include all of the old ones—wood, stone, glass, metal, brick and tile—assembled in new forms.

— Paul R. Williams, from his 1945 pattern book The Small Home of Tomorrow

After World War II, mainstream style trends in residential architecture made a full swing toward Modernism, and the “free plan” pioneered by Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the late 1920s—“the assemblage of freestanding walls and other architectural elements according to compositional and spatial values, virtually without regard to structural necessity”—became the norm.5 In Williams’ case, it was a measured modernism, to be sure. More often than not, his designs were a classically proportioned, traditionalist/modernist mix of large open rooms flowing together in a typical indoor/outdoor California pattern. This mix, so adroitly handled, is key to understanding the timeless quality and continued popularity of Williams’ work. No matter how grand the scale, a residence designed by Williams was, and is, more of a sanctuary than a statement. He practiced expedience with decorum, and built, as he once said, “homes, not houses.” Frank Sinatra, Danny Thomas, Julie London and Bobby Troup, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Jennifer Jones, and Anthony Quinn were all postwar clients.

In the United States an economic boom followed war’s end, and commissions for non-residential work increased exponentially during the second half of Williams’ career: the Crescent Wing of the Beverly Hills Hotel (with its distinctive façade signage in Williams’ handwriting facing Sunset Boulevard), and the Polo Lounge and Fountain Coffee Room revamp inside the original hotel building6; the Botany Building and Franz Hall at UCLA; the Marina del Rey Middle School; the Palm Springs Tennis Club (in collaboration with modernist A. Quincy Jones, who worked in the Williams office in the late 1930s); the memorial pavilion for Al Jolson, the vaudeville colossus famous for singing “My Mammy” in blackface. There were Williams churches, banks, automobile showrooms, courthouses, and funeral parlors—his work was as prevalent in the “flats” of L.A. as it was in the hills. Hotels and apartment buildings in South America bear his imprint, and his many commercial and residential commissions in Nevada include Berkley Square (1954) in Las Vegas—a community of homes marketed to middle-class African Americans. By the time he retired in 1973, over 4,000 projects designed by Williams had been built. He was also part of the team behind the Theme Building at LAX. This structure—so consciously “futuristic” in its conception and realization—is one of the few projects Williams was involved with which today feels dated. Skirting the aesthetic edge of camp, this still-beloved landmark is forever fixed in its receding moment.

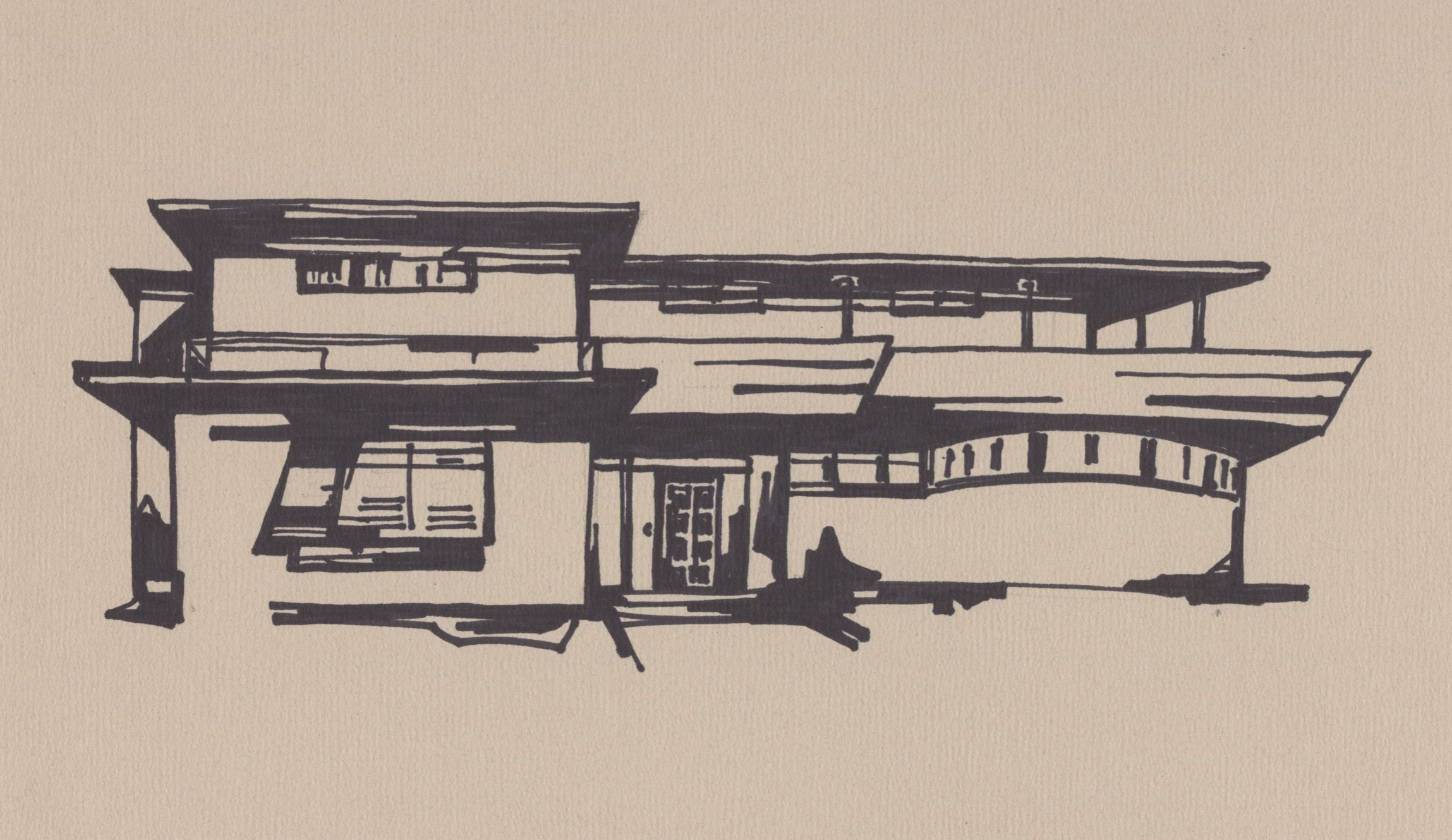

Lafayette Square, a neighborhood on the mid-city plain west of downtown Los Angeles, is a smaller, less-grand version of Hancock Park, two miles to the north. Like Hancock Park, it is filled with towering trees surrounding large, old houses of nearly every local architectural style, any one of which could have been designed by Paul R. Williams and Associates. On a corner lot at the foot of a parkway sits a white, two-story house of horizontal planes, clad in brick, stucco, wood, and glass. This exemplar of “sensible” Modernism is the home Williams designed for his wife Della and himself in 1951. This was the refuge where “he didn’t discuss projects, problems, racial conflicts, or personnel,” where everything in the living room was pistachio green (including the piano and the telephones), and where he and Della lived together until the end of their lives.7 They loved parties and get-togethers of all kinds—although Williams, as a rule, never socialized with clients. The Williams’ circle was made up of African-American men and women of accomplishment whose successes they celebrated and promoted. Civil rights and racial equality were lifelong passions, but Williams’ involvement was strictly on the institutional level. During the protest era of the 1950s and 60s, he did not “sit in” or yell through a bullhorn. (In fact, he was an adherent to the moderate Eisenhower-Rockefeller wing of the Republican Party—a wing that would seem wildly liberal today had it not been expunged by the current GOP for insufficient conservatism.) For this gentleman of the old school—who shattered a barrier of his profession and then went on to reach its heights—it was imperative to set an example by living his life with quiet reason, intelligence, and foresight, and it is impossible to imagine Los Angeles without his contributions.

Published in PARIS LA 12 (Fall 2014), the Alternative Habitation issue.

Notes:

1. Charles Moore, “Schindler: Vulnerable and Powerful,” in You Have to Pay for the Public Life: Selected Essays of Charles W. Moore (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 212. Moore was an architect whose writing is as important as his buildings. His 1984 book, The City Observed, Los Angeles: A Guide to Its Architecture and Landscapes, is essential.

2. Karen E. Hudson, Paul R. Williams, Architect: A Legacy of Style, forward by David Gebhard (New York: Rizzoli, 1993), 57. Hudson is Williams’ granddaughter, and the author of a second monograph, Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style.

3. Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra—students of Loos in Vienna—both left Europe in the early twentieth century and took separate but similar paths (Chicago, Frank Lloyd Wright) before ending up in Los Angeles in the 1920s.

4. Hudson, Paul R. Williams, Architect, 226.

5. Claire Zimmerman, “Tugendhat House, Brno, 1928-30,” in Mies in Berlin (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2001), 242.

6. In May 2014, in reaction to hotel-owner Sultan of Brunei’s adoption of Sharia law in his home country, the film industry—en masse—temporarily abandoned the Beverly Hills Hotel as a location for breakfasts, dinners, charity events, awards banquets, bar mitzvahs, weddings, assignations, etc. To paraphrase the late producer Julia Phillips, you’ll never eat lunch in this town again at the Polo Lounge. The fashion community soon followed suit and the boycott spread to other Sultan-owned properties such as the Dorchester Hotel and 45 Park Lane in London, Hôtel Plaza Athénée and Le Meurice in Paris, Hotel Principe di Savoia in Milan, and Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles.

7. Hudson, Paul R. Williams, Architect, 17.

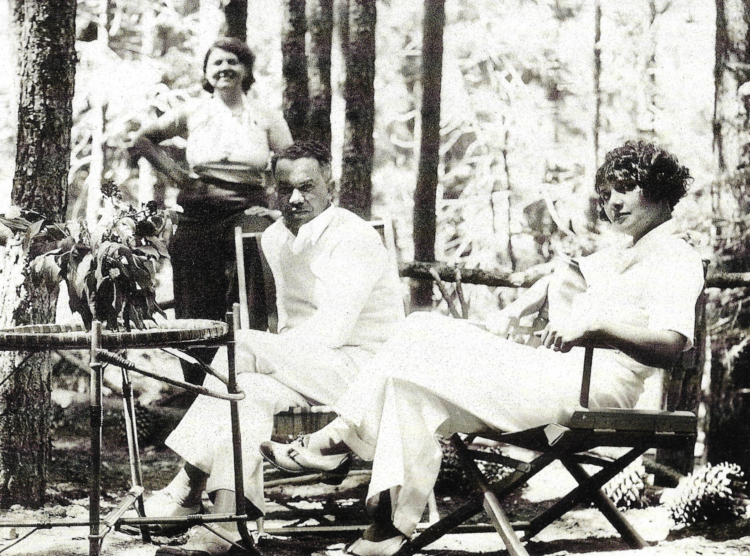

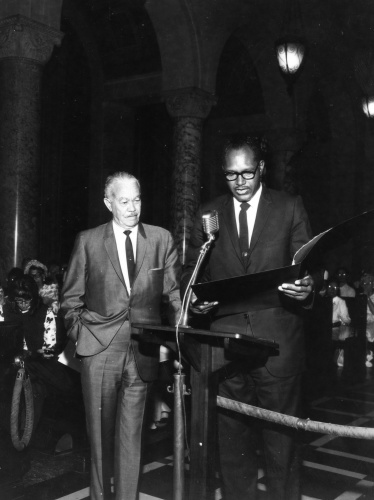

From top: Paul R. Williams, Frank Sinatra residence, Trousdale Estates, Beverly Hills, 1956, all Sinatra residence images courtesy and © the Mott-Merge Collection; Paul and Della Williams (foreground) in the 1930s at Lake Arrowhead, west of Los Angeles, image courtesy of the Paul Revere Williams Project; Paul R. Williams, Cordhaven, residence of Errett and Virginia Cord, formerly located at Hillcrest and Doheny, Beverly Hills, image courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; Paul R. Williams, Saks Fifth Avenue, 1947, image courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; Williams (left) receives the gratitude of Los Angeles from then-councilman, future mayor Tom Bradley, photograph circa 1970, image courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; Paul and Della Williams residence, Lafayette Square, Los Angeles, drawing by Barlo Perry, image courtesy and © the artist; Sinatra residence interior (2).