Things and objects are eloquent. They talk to me. The light, textures, colors—they have a rhythm which becomes a symphony. — Eileen Gray, E.1027

Eileen Gray recognized her good fortune. The fact that she was born into a rich family, she said, allowed her to become an artist. Allowed her the time to consider and develop, at her own pace, an aesthetic well suited to a culture starved for oxygen in the void left by the Great War. A modernism it didn’t know it needed. A clean break, like it or not.

Gray—born in Ireland in 1878, and educated at Slade School in London—moved to Paris in the early 1900s and immersed herself in the creative life of the city, specifically in the study of lacquer under the tutelage of Seizo Sugawara. Opening a shop called Jean Désert in Paris after the War, Gray began making and selling the lacquered screens and early furniture pieces that now figure so prominently in the canon of iconic twentieth-century design.

Soon tiring of designing mere interiors, Gray was inspired by her lover, the architect and writer Jean Badovici, to realize a house in which to stage them. Not trained in architecture, she read and traveled widely to research her newly adopted field, focusing on works by architects with whom she was already in aesthetic tune—Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Gerrit Thomas Rietveld, and, inevitably, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier).

Like his buildings, Corbusier’s persona manifested as a form of intrusion. His houses were self-styled “machines for living”—the architectural equivalent of the dress wearing the model, instead of the other way around. While Corbusier’s influence did lead to an even greater spareness in Gray’s work, she pushed back against the prevalent mechanization of the time, tempering her modernism with a palpable human presence, insisting that the feelings and desires of those inhabiting a house be given greater consideration.

Built between 1926 and 1929 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin—east of Monte Carlo—E.1027 was designed as a place where important artistic work and a life of domestic tranquility both had a home. And for the two short years Gray and Badovici lived there together, it was a dream. Years later, Corbusier came to stay and, with Badovici’s consent, “defaced” the white walls of E.1027 with his murals. Jealous of Gray’s masterpiece, Corbusier even declined to correct those who assumed E.1027 was his creation. But by then, Gray had long since moved on. “I like doing things. But I hate possessing them.”

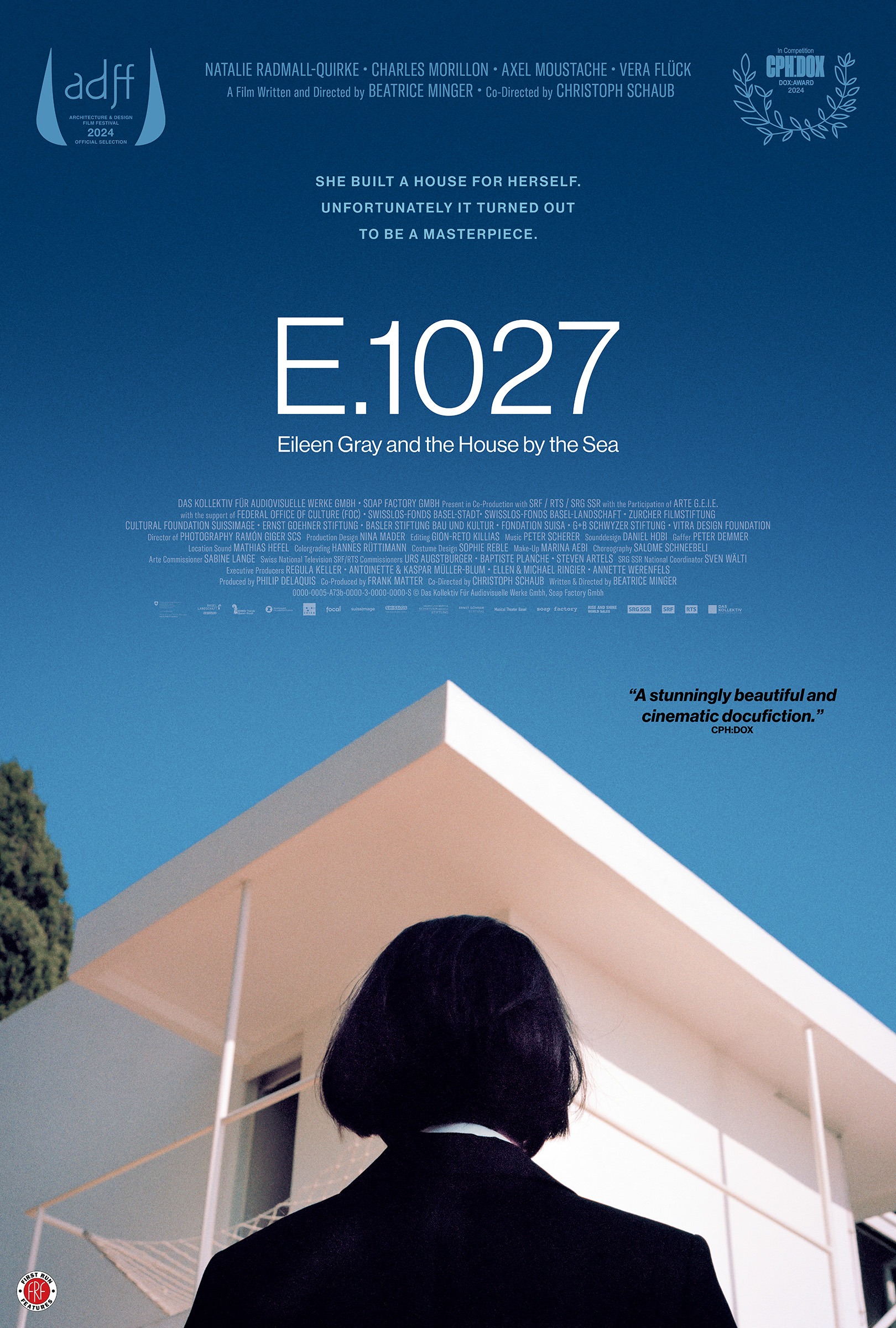

The new film E.1027: Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea, written and directed by Beatrice Minger and co-directed by Christoph Schaub, presents abstract portrayals of its leading figures—Natalie Radmall-Quirke as Gray, Axel Moustache as Badovici, and Charles Morillon as Corbusier—combined with archival footage and narrative voiceover. Shot on location at E.1027, this feature-documentary hybrid matches the sleekness of its setting—its serenity, its surface poetry, its fragments of grace.

See info and link below for screening details.

E.1027—EILEEN GRAY AND THE HOUSE BY THE SEA

Written and directed by Beatrice Minger

Co-directed by Christoph Schaub

Through May 29

Royal

11523 Santa Monica Boulevard, West Los Angeles

laemmle.com/e1027-eileen-gray-and-house-sea