MANUSHKA MAGLOIRE

HEAD OF PARTNERSHIPS, FOR FREEDOMS

in conversation with DOROTHÉE PERRET

May 2022

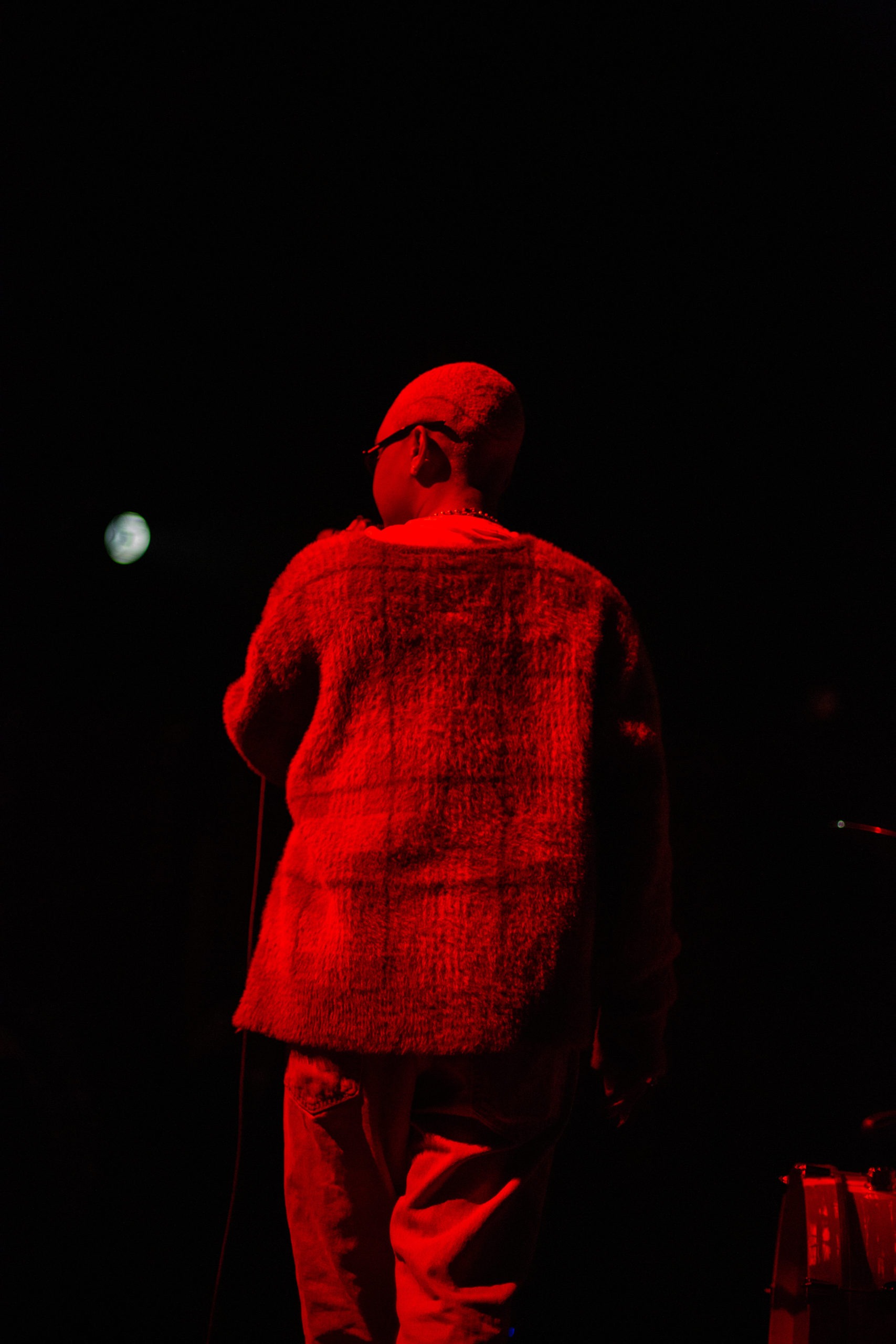

Bringing an activist, justice-and-democracy-centered commitment to her expertise in marketing, project management, and consultation, Brooklyn-based Manushka Magloire is the Head of Partnerships for the arts organization For Freedoms. In Los Angeles for the autumn 2021 Hear Her Here pop up activation in partnership with Black Image Center, The Black Family Archive, and Converse—a celebration and exhibition of the work of Black femme artists—Magloire spoke with PARIS LA editor Dorothée Perret about the power of art and the evolving mission.

DOROTHÉE PERRET — I’m really thankful and grateful to be able to talk with you about For Freedoms and the Hear Her Here project, an ongoing initiative. For Freedoms is kind of the umbrella of the many intervention projects around the nation. But not only here, right?

MANUSHKA MAGLOIRE — For Freedoms was founded ahead of the 2016 elections here in the United States, and has produced global activations since our inception. We think about For Freedoms as a collective, artist-led organization that really stands firm in the belief that art is here and serves to wake us up, to expand how we think about concepts, ideologies, systems we operate within. It also helps us grow beyond our current structures. So, really, it is also about centering the voices of artists and thinking of artists as first responders—especially in public discourse. And again, when we think about 2015, 2016 here in the States—when Trump first threw his hat in the ring and was running for the presidency—this was the inception point to really look at how we leverage art and creativity to expand and broaden what it looks like to get involved in day to day democracy and civic life, from the very specific lens of art does not need to be removed from this conversation. Art should have a place at the table and be part of the discourse in local, national, and global politics. It’s not something that should just be in a museum or on your screens—it’s a way of life. Since 2016, we’ve run a few national and global campaigns that have intersected a lot of elections here in the United States but also sparked a new way of thinking about, “How do we leverage advertising mediums in a different way?” And by this we mean billboards, so we launched the 50 State Initiative, which is where, in the fifty states—and D.C., Guam, Puerto Rico—we had billboards that were taken over, essentially, by artists across different disciplines and mediums that forced us all, collectively, to interrogate politics.

It’s not only artists of color. You bridge, it’s a cross-conversation, right?

Yeah, that is the main point. It’s a provocation, it’s an interrogation. Art is meant to have us look within, and we can look within collectively, right? It’s not necessarily dictated by race, creed, gender. Artists are artists. We actually operate from the space of: Everyone is an artist. We welcome participation, and we activate our network of artists across different mediums, museums, schools. We work with civic organizations, leaders—corporations as well. For us it is the many, it is the sum of all of the parts. We don’t want to make art feel like something that’s not accessible, or it’s only elite, especially when we think about fine art. There’s a way for us to place this work, again, in the center of our cultural lives. It shouldn’t be a separate thing.

In the public discourse. You do that through visual art, through the billboard campaign, but you’re very famous for the AFROPUNK Festival.

[Smiles] Oh, me, personally.

AFROPUNK has nothing to do with For Freedoms? Okay, I mixed them up…

No, it’s okay.

The two seem to [relate to one another]…

Prior to working at For Freedoms, I was Director of Global Director, Social Impact & Community at AFROPUNK music festival and we began to collaborate on artwork activations and Get Out The Vote activities. Hank Willis Thomas—one of the co-founders of For Freedoms—has been a close, personal friend for many years. So when he told me he was working on For Freedoms, and what the idea was—before it even started—I said, “Okay, let’s do this at the festival.” Some of the first public launches of the billboard artworks—they were not on billboards, they were on canvases— was at the 2016 AFROPUNK festivals in Brooklyn and Atlanta. This was a way for me to [combine] my personal and professional work. We were doing a very strong push at the time at AFROPUNK to mobilize our audience—people who were coming to the festival and beyond—to become more engaged in civic work, more engaged in the elections and getting registered to vote. This was a way to leverage culture and art in a way that made sense to people. In a way that wasn’t preaching, that really was looking at: “This is what’s going on in our world, here’s how we can make you feel something about it through a visual lens, and the creativity of art, in the hopes that this would incite some level of action from you.” So, in a way that is where my relationship with For Freedoms started.

I’m curious to know how projects are created within For Freedoms. Are they initiated within the broad community? Do people come to you with ideas and you’re willing to support them?

Yeah, it’s very much of a collaborative nature. We think about creativity and the work that artists are doing as a value. It’s society’s value system—it’s part of it. And it’s important that artists are a part of creating new ideas, reimagining new ways that our systems are built. A lot of the time what that looks like is people have an idea and they want to work with us. Or they’ve already started an initiative or program and they want to be able to collaborate [with us]. Honestly, when I think about it, it’s like a gumbo of community, of organizations, of museums, of independent artists just being, “I want to work on this, and I would love to partner with you and your network in order to help bring this idea from my brain”—or the canvas, or whatever medium it is—“out into the world.”

And you also work with the support of brands, so how do you manage to bring in the brands, which sometimes have a bad reputation [which then] becomes a political engagement? They’re always on the profit side and not always looking out for people’s best interests. How do you manage to keep a fair balance within all the projects?

Which is really important to us because, for us, part of this work—when we’re thinking about brands and corporations—is also thinking about new models. How do we model new ways of thinking about brands and not making them so vilified, right? We all have a bit of that cringe, like “You’re going to come in and it’s just capitalism and you just want logos.” The only way to eradicate and change the dynamic of these relationships is to model doing that. Go in and have the opportunity to speak with like-minded people that are working at these brands. When we think about corporations, they are still people who are powering this thing.

Exactly.

There are people within these rooms, within these hallways, within these little screens, and you just need to find the right people that are going to champion and are interested in divesting from business as usual. That’s all it takes. You just need one person who’s willing to push things along the way. We’ve been lucky enough to work with challenger, disruptive brands, like Converse, on really interesting programming that is meant to impact people. Yes, it still has to drive back to some level of the bottom line because we do operate in the system of capitalism—that’s just where we operate.

It’s also a predominant white and patriarchal system, so how do you navigate that?

I think we always come from the space of: How do we remix, revamp, re-energize ways in which people do business and partner together? For Freedoms is really interested in having new economic models, for ways that we provide more financial growth and education for artists as well. The idea of artists’ sovereignty and the fact of being a starving artist and/or having your work not valued until the powers that be decide that it is? We’re not interested in upholding those old ways of doing things. It is important to us that we are working with brands that understand that if you’re coming to us, we are not an agency, we are not here to be hired. You know, you cut a check and we deliver a campaign. That’s not the work that we do. We collaborate, from start to finish, with the people we collaborate with. That means, if Brand X is coming in, you can’t just give us a brief and then we give you a pitch. That’s not who we are or how we work. We bring in artists [and] we discuss the fact that it is important and imperative to us that we value the work of our people and artists and we value it above anything else. Whatever the market rate you’re used to paying for licensing something or working with somebody? What’s going to happen here is double, triple, quadruple. Because our north star is always the importance of valuing exactly how art and creators are to be in every room, at every table, if we ever expect to see new ideas, new change, new innovation, new ways of talking to people actually take hold.

It’s got to be a mission-and-value aligned way of working. That means there’s a lot of people we don’t necessarily work with—we just don’t speak the same language. Generally, people who seek us out understand the point of view where we’re coming from, so they’re already at step #1 with us. They know what they’re getting, so that makes it an easier conversation and a way in which we can learn about one another. I think that’s also the important thing about how we all work—we’re all curious. We don’t necessarily think that just because a brand is selling a thing that that doesn’t mean there aren’t other ways to make an impact and push outside of our own comfort zones and help bring others outside of that too. It’s important to have that give and take and that space to talk about, “Here’s who we are and what we’re about. Are you down? No? Okay, cool. If you are, great! Let’s play.” We also like to imbue a lot of play and joy in how we approach our partnerships and conversations.

Do you feel the culture is changing?

Yeah. It had no choice but to change.

The Hear Her Here project is very specific to one neighborhood in Los Angeles, right?

It’s specific to neighborhoods in L.A., but it’s specific to L.A.

I went to the event in Leimert Park, an historical neighborhood in the Black community. That’s where the kick-off took place, right?

Correct. There’s a total of five murals and we’ve got two murals in Leimert Park in partnership with the organization called Community Build, which was founded by Rep. Maxine Waters in, I believe, the early 1990s. The history of that particular organization and being able to partner and work with them is not lost on us. It’s very important that a lot of this work and collaboration with Converse is multidimensional. It’s inspired by Black female creatives and artists, but it’s also to celebrate these voices and these perspectives and these stories. The intention of this project is to create more spaces for visibility and centering Black women creators. It is about listening to these creators, to their stories. It’s also about elevating how we access art and what we consider to be art. And where does art show up? When you take fine art and you put it out literally for the people to access at any point in time, that changes the dynamic of thinking about fine art as enclosed in an ivory tower, gallery, or museum space. When you’ve got it on a community organization in the middle of Leimert Park, this prioritizes that everybody has access to it. It changes the way in which you think about your community, your neighborhood, what it looks like. For us, it’s really about making sure we’re championing for different voices. We want to connect and have people exchange, to look at local spaces as a different way of activating them, of bringing them alive. So, we’ve got two murals in Leimert Park, we’ve got one in Inglewood, and we’ve got some in Crenshaw that are going up right now.

You bridge art and politics in many ways. Hear Her Here is also about archive-building for many Black communities. Archiving is an important part of Black history that maybe is missing in some places?

Yeah. There are so many little arteries to Hear Her Here. Providing the artwork itself is a canvas for conversation, right? This allows for an invitation for everybody to listen and learn. This is how we explore Black vision, how we explore Black voices, Black stories. There’s a reason why we’re placing all of these murals [where they are], why it’s so important and why it has such the level of impact that it does. We want to activate joy and create spaces for us to explore what joy and rejoicing look like for Black communities. At Community Build we also have a programming component to this work and it’s where we are identifying and working with young Black female creatives to help create a pipeline for spotlighting and highlighting their work and their talents and helping to create a road map and a tapestry of support—both professionally and personally for these young women and femmes. We also worked with a collective called Black Image Center. There’s about five or six [collective members], primarily young Black women—there are two gentlemen that work with them. We’re investing in the impact of the work that they’re doing. The Black Image Center are visual artists—they’re photographers [including analog photography], that’s their medium—and they started this collective because they noticed there wasn’t enough access to tools and resources as photographers in their local community. They couldn’t find anywhere to get film, they couldn’t get their work developed properly, it just wasn’t accessible to them locally. They realized there was a gap in services, if you will, and decided to do something about that. Over the course of the pandemic they created community fridges and mutual aid fridges that were around photography supplies, specifically film. So, you could come in and get free film as a photographer from a fridge, for everybody. This developed into a bigger idea when we met them. They wanted to create a Black Family Archive. And they wanted to look at, “How do we preserve the history and heritage of our community in this hyper-digital world?” There’s the passing of information at the speed of light across the internet and social media, and there’s still this gap generationally. There’s not a lot of intergenerational conversation happening and they really wanted to zero in on that and bring in families and conversation and the art and practice of the preservation of our images and our stories and that narrative and how important that is. So, the launch we did at Community Build was all around the Black Image Center and that Black Family Archive. And now they are opening their headquarters to offer these resources more consistently—film fridges, photography workshops, community space, and eventually a darkroom.

By being able to work on what was originally just a mural program, and you dig down even deeper, you get to unpack so much more, and that’s the purpose of Hear Her Here. We start with that mural, that artist’s work as that canvas that opens up the conversation to listening to what else Black female creatives want to do and how they want their work out in the world and what they want to say. And how they want people to interact with what they’re putting out in the world. I was there [at the Leimert Park event] as well. I live in New York and I flew in for that launch, and [was] able to see a mother and daughter, an aunt and a cousin coming in with pictures and talking about what this person meant in their family, watching the archival process happening, learning about different neighborhoods in… St. Louis. I happened to be there when Hana Ward, one of our mural artists—her mural is at Community Build—came in with her mom, and I overheard her mom talking about a picture of a man, I think the first Black doctor in his neighborhood at the time in St. Louis. And her having that image: “Oh, I forgot. He was our neighbor.” It’s like listening to our griots being able to tell us, You honestly don’t know where you’re going unless you know where you’re from. That was the very real reminder of why archiving is so crucial, so special, such a treasure and a gift—to be able to access this amazing storytelling and narrative that nobody can revise, nobody can take away, there’s the physical proof of You are here.

It’s true stories about real people, it’s not about famous people, it’s about everyday life. That’s the beauty of the project—it really touches all of us. We are all, in many ways, interconnected. When you feature these stories, we all benefit and learn from it. What’s the next chapter for Hear Her Here? Is there a specific project coming up, or something more general with For Freedoms?

For Hear Her Here we also had a focus on an intimate salon series, so there’s smaller conversations that are happening between mural artists and young black femmes creatives out in the world. Again, it’s that intergenerational share. There’s the young folks who are just at the beginning of their career, and then there’s some folks who are a bit further along. Having the opportunity to create these spaces for conversation—not, like, “Let’s have a panel,” but an actual kitchen-table talk, the same way as if you were with your girlfriends. You’re sitting and just talking about the things that matter to you, that you care about, that you’re asking questions about. We are now celebrating this cohort and hope to develop this into a true professional mentorship program and how that works and correlates directly with Converse. And some of us, as our larger network of For Freedoms, are asking, “How do we help provide sustainable opportunities for our young artists to live and create?” That’s very important to us and always going to be at the center of the work that we’re doing. So, some of the 2022 work is doing the strategy and planning around, “What are those things we want to see happen, how do we make them happen?” So that’s the framework for where Hear Her Here is going into 2022. Converse has been a really dope partner, which is always great. We worked with them before as For Freedoms on a get-out-the-vote campaign in the fall. We worked with Denim Tears, with Tremaine Emory, so that was like our first introduction. Honestly, both parties were like, “Yo, this is great. We want to do more work.” Which is how we wind up creating Hear Her Here, and I think this is how we want to continue to approach working with corporations and brands. We’re not interested in these one-off things, we’re not interested in you being able to slap a logo on something and say, “Hey, we did something cool.” We want the sustainable ecosystem that feeds itself, that allows for more people to come into the fold, to come into play, and how do we continue to expand and grow. On the For Freedoms front, it’s the same thing, to be quite honest [laughter]. Our priorities are around a campaign called Another Justice: By Any Medium Necessary, which contains a series of initiatives. The Another Justice billboard campaign, looking at carceral justice, even includes an artwork from one of the young cohort members, Brianna Mims. Hear Her Here is one of the projects that falls under Another Justice, and it’s really about exploring and interrogating what justice is to us, as a people. What does that mean? We’ve been conditioned and socialized to think about justice in very binary ways—good versus evil.

Like a lot of things with the Western culture.

Right versus wrong. It’s really more nuanced and complicated than that, right? Part of how we’re hoping to explore what justice means and reimagining justice, collectively together, is through projects like Hear Her Here, through some of the other work we’re doing through AAPI [Asian American Pacific Islander].

The four freedoms give a bond to the organization.*

Yeah, it does, it is. It’s our compass, it’s our map. When we think about how we invite radical imagination, how do we reset conversations and systems, how do we rebuild on the basis of love and community care, these four freedoms, for us, are sort of like the anchors that help to provide the scaffolding for how we talk about these things, how we direct how we’re talking. It’s listening, it’s healing, it’s awakening, it’s justice. And these are big nuances.

This is very American, no? It’s at the root of the American nation. Do you embrace this idea?

That’s a good question, Dorothée. It’s based on the American experiment and we have to think about it from that lens. Things feel so constricted and structured that we forget that this is an experiment. A lot of the laws that we are currently living under are only a few decades old. They’re not hundreds of years old. That means that there is absolutely the power to reimagine them, to reset them, to shift the perspective of how this experiment wants to move. And I think that I will always have a healthier-than-not perspective, on most days, that there is power in experimentation. And if we give up on the idea that we can push beyond these boundaries, we’ll continue to remain in this vicious cycle of injustice, of racial inequity, and bias.

White supremacy. Let’s call it by its name. We see it every day in the news. This young guy who killed last year [in Kenosha] getting out with a free ticket. It’s every day in this country that we witness it. It’s painful and that’s why the work you do is extremely important. It helps to realize that there are ways to make change. And it’s real—it’s real engagement with real people. It’s real stories, it’s real history, and that’s necessary to…

Yeah. This is why we’re trying to shift the perspective of artists as essential workers when we think about what essential workers are and are doing from the lens of Covid and what we all collectively went through. Art is an essential tool for pushing us to rethink how things are working and not working, and to activate us. As long as I’m breathing and alive, I have to be able to know that I can have a reaction to a thing, whether good or bad or anything. It’s the thing that makes you human, right? I feel. I feel, therefore I am—forget about I think therefore I am… I feel.

Relation to me is really important. We’re not just single individuals—we relate.

There’s so much power in that. And we can’t lose sight of that power, because the structures and the systems were meant to keep us docile and not try to access that power. That’s why we need our artists and we need our creative lens and we need our collective vision to just be like, Oh, shit, right, I can’t forget that part. I am here, we are here, we can do something about this.

*For Freedoms expands on the concepts and structure articulated in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms Speech,” the 1941 State of the Union address, delivered less than a year before the United States entered World War II. Roosevelt cited freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear. For Freedoms’ “New Four Freedoms” are awakening, listening, healing, and justice.

LINKS:

Learn more about Hear Her Here and visit the Hear Her Here murals.

Learn more about the For Freedoms Another Justice campaign and follow For Freedoms on Instagram.

From top: April Bey, mural, © April Bey; Hana Ward, mural, © Hana Ward; Adee Roberson, mural, © Adee Roberson, with Manushka Magloire (foreground left), friends, and associates, Los Angeles, 2021; The Black Family Archive, a pop up activation by Black Image Center, a Hear Her Here project in partnership with For Freedoms and Converse, Los Angeles, 2021, photographs (7) by Solomon R. Henry. Images courtesy of For Freedoms and Black Image Center.