STEVE LEHMAN — EX MACHINA

By Yann Perreau

I became a fan of alto saxophonist and composer Steve Lehman the very moment I listened to his music for the first time. His album with the Senegalese hip-hop band Sélébéyone, his opus with his trio and Craig Taborn, The People I Love—these are the kinds of works that I wish I could go to a desert island to listen to, with no interruption, for as long as possible. Then, last fall, I attended the event Lehman organized at REDCAT in celebration of the great Anthony Braxton. While experiencing this astonishing concert, I remember thinking that I could finally understand what improvisation meant. The sextet put together by Lehman—a former student and longtime collaborator of Braxton’s—included bassist Mark Dresser, trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson, tenor saxist Mark Turner, drummer Jonathan Pinson, pianist Paul Cornish, and Lehman himself. During the second half, the frenetic, sprinkle-stabbing duet of David Rosenboom and Vicki Ray took the stage, the former raising hands to the latter who answered by conducting the dozens of Cal Arts alumni musicians into unknown musical territories. Not only was I able to appreciate the math and science underlying Braxton’s oeuvre—his “real-time collage of compositions”—I also enjoyed the spontaneity, humor, and rule breaking at the core of his art.

After that memorable night, I got into Lehman’s 2009 Travail, Transformation and Flow. This landmark album, the New York Times number-one jazz CD of its year, opened a new chapter in the history of recorded jazz. It drew its inspiration from spectral music, a school of contemporary music in France that Lehman describes as “a way of looking at the physical properties of sound and the nature of timbre.” Because of the nature of sound, he explains, “we hear a single note, an F-sharp for instance, but there’s a whole spectrum of frequencies in fact that are sounding at the same time. That’s what gives a sound its color, if you like.”

It took sophisticated technology and computers to evaluate and analyze this in the 1970s and 1980s, and for pioneers like Tristan Murail to create music from this research. But it takes Lehman’s talent to transform these ideas into exhilarating, thrilling, and brilliant music. Besides the instrumental overtones which create striking new harmonies, Travail offers unforeseen, exceptional rhythms. Lehman explains that his father, a talented trumpeter, passed away when he was just eight years old. He grew up listening to his dad’s record collection, “as a way to try to connect with him and cope with him not being around.” He also got into hip-hop, which was the big thing at that time in New York as well as in Connecticut, where his family was living. The unique blend of contemporary, spectral music, Coltrane-like jazz impros, and hip-hop pulses, breaks, and rhythms defines Lehman’s style.

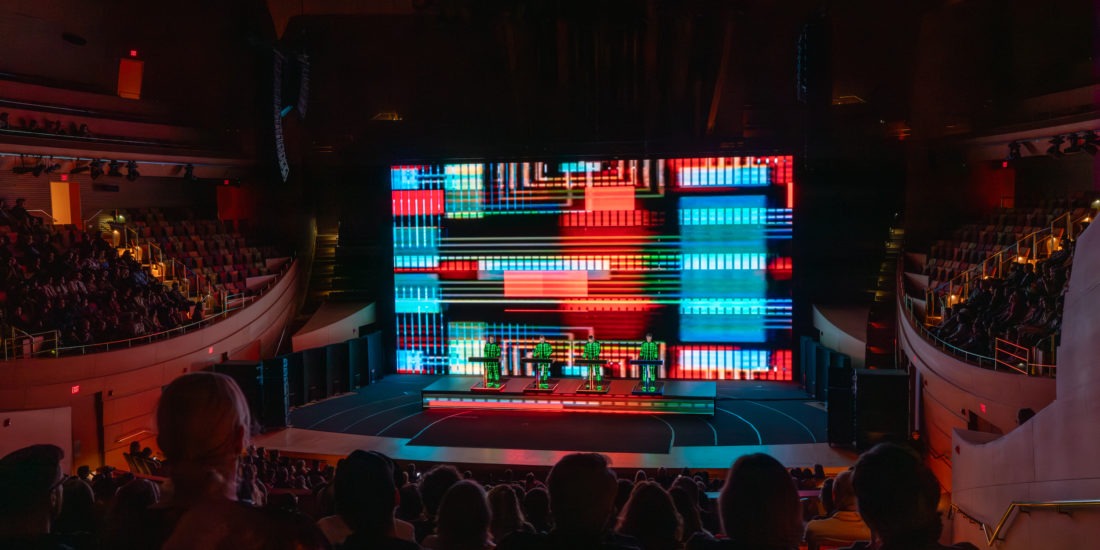

Listening to Lehman’s latest album, Ex Machina, brings my admiration for his music to another level. Developed in France at IRCAM (the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music) and recorded outside Stuttgart with members of the Orchestre National de Jazz, this work also involved Dicy2, an AI software developed by researcher Jérôme Nika. Soloists interact with Dicy2, which was also used as a pre-compositional tool and integrated directly into the overarching concepts of orchestration, rhythm, and form. What comes out of this experimentation is, first, great music. The intriguing pattern of “39,” the intro piece, brings you into a fresh, mysterious, almost film noir mood as if you were in a twenty-first-century version of Godard’s Alphaville. “Los Angeles Imaginary” would speak to anybody who knows this city, the music travels like a furious car in the megalopolis, zigzagging into highways, then slowing as if to crawl into back alleys. Its hiccup, distinctive, and precise rhythms capture the beat of the city. The dialogue between computer music and cutting-edge improvisation is at its best in “Le Seuil, Pt. 1,” while the sensual “Jeux d’Anches” grooves in a love parade between Lehman’s distinctive alto’s solo and a frenetic keyboard.

One wonders throughout the album which part is played by the computer and which by the musicians. Not that it sounds in any way “mechanical”—improvisation and spontaneity are the signatures of Lehman and his partner in crime for this album, ONJ artistic director Frédéric Maurin. The album was recorded in a studio with concert-style conditions, so that everybody involved had to perform, feel the music, and take a chance or risk. “I’m a jazz musician,” explains Lehman

I’m an improviser. So I’m always thinking: What is the musical environment going to be for the soloists? It’s hard to have an original approach to melody, harmony, and rhythm. On top of that, you must think as a composer working in modern jazz idiom: what is all this going to mean for the person soloing? Are they going to be able to engage with the materials? Are they going to be inspired to not only play well but maybe be challenged a little bit?

The result makes me think of action painting. It’s raw and honest, the movement or gesture performed by each musician is essential, and the music becomes the trace of a unique action that took place very fast.

Lehman confesses many challenges posed by Dicy2, moments of frustration, deception, and sometimes astonishment. What better kind of music to explore the possibilities of AI than this one, which is all about improvisation? Furthermore, his instrument and the way that he plays it are probably the closest to a human voice that one can find. No machine could ever replace this. And that’s good, as it’s not what Lehman ever used Dicy2 for. As with most creators who use AI in an intelligent way, this software has opened new possibilities for him. “I would ask Dicy2, ‘I want to orchestrate this electronic sound for two trumpets and two trombones.’ And the software answered OK, well, here’s 20 different ways to do that. Something that would have taken me maybe like two hours or something to write that thing. And that meant that I could devote my energy and creative ideas to something else because this is already taken care of.” Can a computer improvise, as only talented musicians do? Probably not, and that’s what Lehman perfectly understood by studying with George Lewis at Columbia University. He understood how to go beyond the man-versus-machine binary way of thinking about computer music. “These new technologies force us to see why that computer-made idea doesn’t sound good, or what is it that I can bring to the table and can’t turn into an abstraction for the computer. Ultimately, in the best scenarios, it reflects on what makes us human.”

See:

https://pirecordings.com/albums/ex-machina/

https://stevelehman.bandcamp.com/album/travail-transformation-and-flow

https://www.redcat.org/events/celebrating-anthony-braxton

From top: Steve Lehman, photograph by Sarah Desage; Steve Lehman with the Orchestre National de Jazz under the direction of Fred Maurin, photograph by Sylvain Gripoix.

Images courtesy and © the artists and photographers.