RIGOLETTO AT LA OPERA — MASKS, POWER, AND THE ECHO OF FASCISM

By Yann Perreau

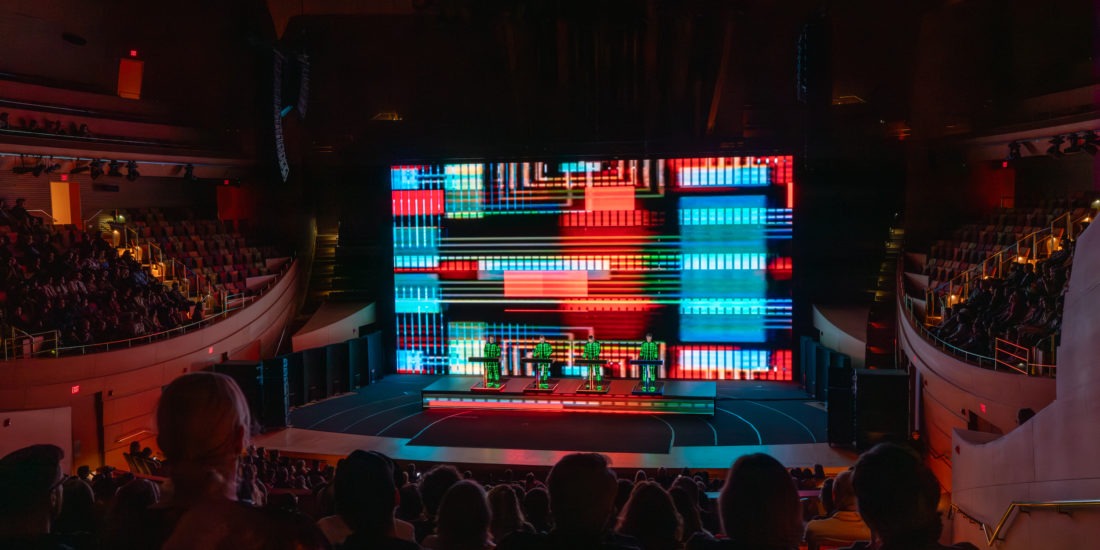

When the curtain rises on Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto at LA Opera, the audience is confronted by a surreal and unsettling tableau: around thirty masked men in suits, standing in tight formation, their faces obscured by animal visages and commedia dell’arte grotesques, stare back at us with unnerving stillness. We are transported to the Duke of Mantua’s palace amid a lavish ball, but this ball feels more like a tribunal. The men, frozen in place, are less celebrants than enforcers—obedient servants to power.

Then enters the fool: Rigoletto. A clown by trade and function, his painted face evokes the chilling grin of the Joker in recent pop culture. He is one of them, but not—a jester whose power comes from proximity, but whose mask is fused to his skin. The Duke, meanwhile, is busy plotting another conquest. He chats with Borsa: “Della mia bella incognita borghese / Le feste ognor rammento…” (“That beautiful unknown girl… I always remember the party when I first saw her…”) “È mia costei…” (“She will be mine…”)

They laugh as they plan the seduction. The courtiers, watching, join the joke, mocking the woman’s father—and so does Rigoletto, sealing his fate. That father, Monterone, is brutally stabbed to death by the masked courtiers, a collective execution carried out by the mob of power. No justice will come on this earth for this innocent victim. His only legacy is the curse he hurls—not at the Duke, but at Rigoletto, the jester who laughed too loud and sided too long with the strong.

With that, the masks onstage acquire a deeper weight: symbols not of festivity, but of cowardice, hypocrisy, and complicity. Director Tomer Zvulun makes this explicit, writing: “The idea of masks/personas is prominent in this production, especially as it relates to society (presented by the chorus)… Throughout history, different people committed terrible atrocities behind masks. KKK hoods, Nazi uniforms, terrorist scarves. Our past and our present are full of examples of the license to kill behind a mask. The question is, what lies underneath?”

Great works of art often allow us to reflect on the present from a safe distance. But here, that distance collapses. Watching the masked chorus terrorize the powerless onstage, I couldn’t help but think of the masked ICE and DHS officers who, over the last ten days, have arrested and detained undocumented individuals across Los Angeles.* Nor can I stop thinking about the real people detained last week and brought to a federal prison just blocks away. Outside this opera house, downtown Los Angeles has been engulfed in protests, riot gear, and nightly curfews.

The next scene stumbles: the sex workers dancing around the Duke seem to have stepped out of Moulin Rouge. The critique of fascist aesthetics becomes less legible unless one has read the director’s notes. Zvulun cites Otto Dix, George Grosz, Federico Fellini, and Luis Buñuel as key influences, grounding his production in the grotesque and the absurd. The visual world, designed by Erhard Rom, draws on the fascist pageantry of Italy in the 1920s and 30s, replete with monumental columns and grand, crumbling walls. Perhaps this is a matter of timing. The past week’s disturbing theater on the streets of Los Angeles still clouds our perception.

Eventually, Zvulun’s concept takes hold. Fascist regimes—Mussolini’s Italy, Pinochet’s Chile, Franco’s Spain, Bolsonaro’s Brazil, Trump’s America —rely on theatricality, spectacle, and kitsch, with the aesthetics of decadent cabaret style co-opted to both distract and seduce. This fusion masks authoritarianism behind a veneer of entertainment, transforming transgression into a tool of control and aestheticized power. In these systems, people live amid a strange blend of frivolity and fear, obsessed with sex and violence, wrapped in nostalgia for a glorified past. On Rom’s stage, that nostalgia takes form in the references to Rome—imperial columns and oil paintings alluding to the Mussolini cult.

As the opera progressed, and as I processed the chaos still lingering just outside the opera house, the relevance of this staging settled in—a masquerade not just onstage, but in the world around us.

Verdi based Rigoletto on Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’amuse, a play so politically dangerous that it was shut down after a single performance in 1832. Both works expose a fundamental truth: absolute power corrupts absolutely. The king—or here, the Duke—does as he pleases. He seduces. He punishes. He remains untouched. It’s impossible not to think of the No Kings rallies that took place the very week I attended the opera, and the wannabe king who currently sits at the White House.

“He is crime. I am Punishment,” says Rigoletto, convinced he has avenged his daughter by killing the Duke. But it is not the Duke who dies—it is Gilda, his daughter. The predator walks free. This is what haunts in Rigoletto: the masked aggressors are never held accountable. The victims are alone, silenced, and unseen. And this, tragically, mirrors the quiet terror faced by undocumented people in our city—in homes, in jobs, in spaces journalists cannot reach.

“I could write another Othello, but never another Rigoletto,” Verdi once said. He was 74, with Il Trovatore and La Traviata already behind him. Under the baton of maestro James Conlon, this co-production of Houston Grand Opera, Dallas Opera, and Atlanta Opera surges forward with tragic grandeur. The music, rich with the lyrical beauty of 19th-century Italian opera, contrasts sharply with the ugliness on stage. Quinn Kelsey (Rigoletto) and Lisette Oropesa (Gilda) are unforgettable. Their duets—intimate, heartbreaking—remind us that love exists in even the darkest of worlds.

RIGOLETTO

Giuseppe Verdi

LA Opera—Final Performance

Saturday, June 21, at 7:30 pm

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion

135 North Grand Avenue, downtown Los Angeles

*On June 16, 2025, California Senate Bill 627—the so‑called “No Secret Police Act”—was introduced by State Senator Scott Wiener and State Senator Jesse Arreguín to prohibit law enforcement officers from wearing masks or face coverings during routine duties, and require clear visible identification. It specifically responds to the June 6 immigration raids in Los Angeles, where masked agents in unmarked vehicles detained more than 100 people—sparking protests over “secret police” tactics and community fears.

Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto, LA Opera, conducted by James Conlon, May 31–June 21, 2025, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, from top: Quinn Kelsey as Rigoletto; René Barbera as the Duke of Mantua; men of the LA Opera Chorus; Lisette Oropesa as Gilda, and Kelsey; Kelsey (far right); Sarah Saturnino as Maddalena, and Barbera; Blake Denson (rear center) as Count Monterone, and Kelsey.

Photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy the LA Opera.