MEMORY’S DRAFT —

JOEUN KIM AATCHIM

IN CONVERSATION WITH DOROTHÉE PERRET

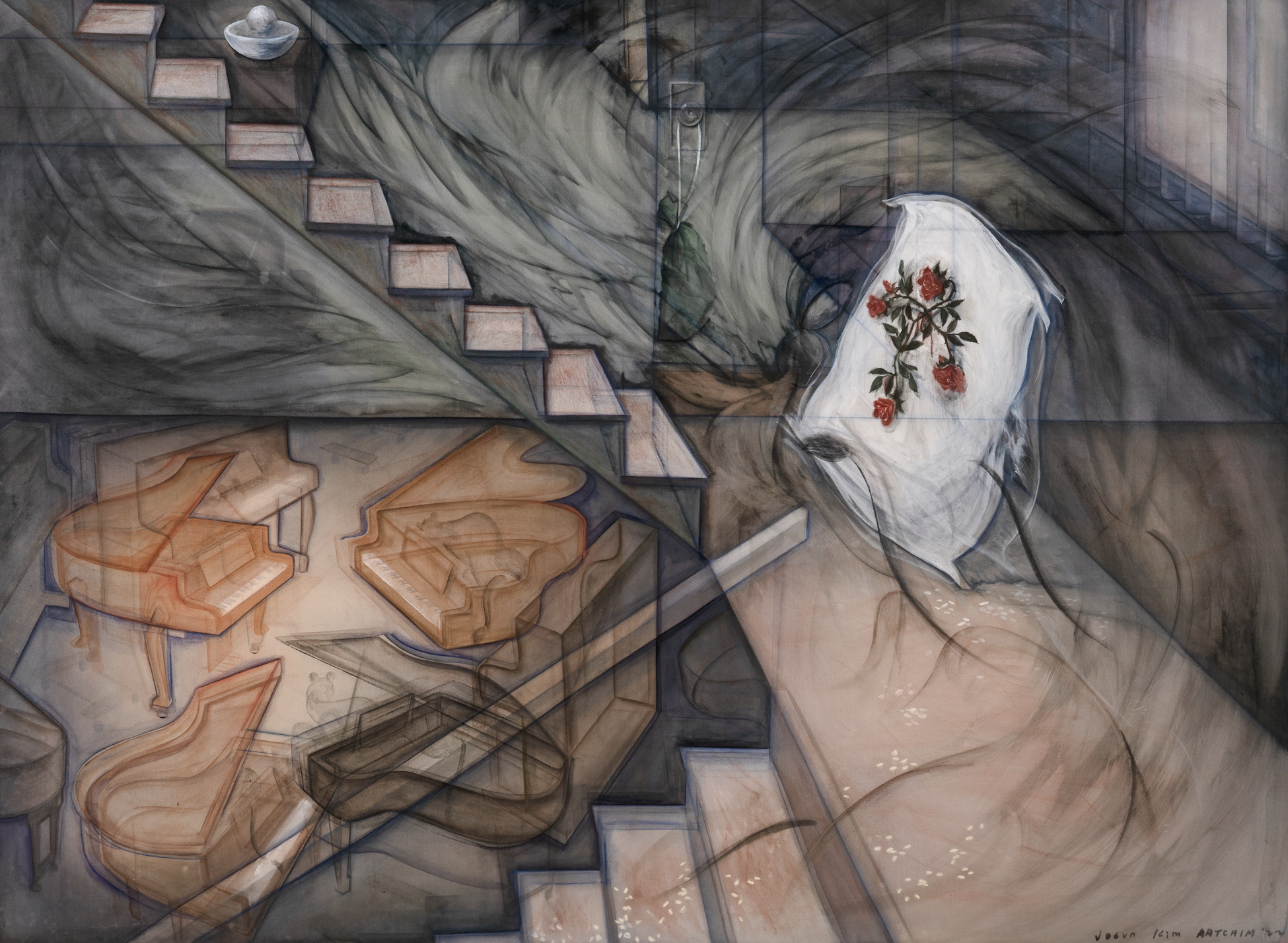

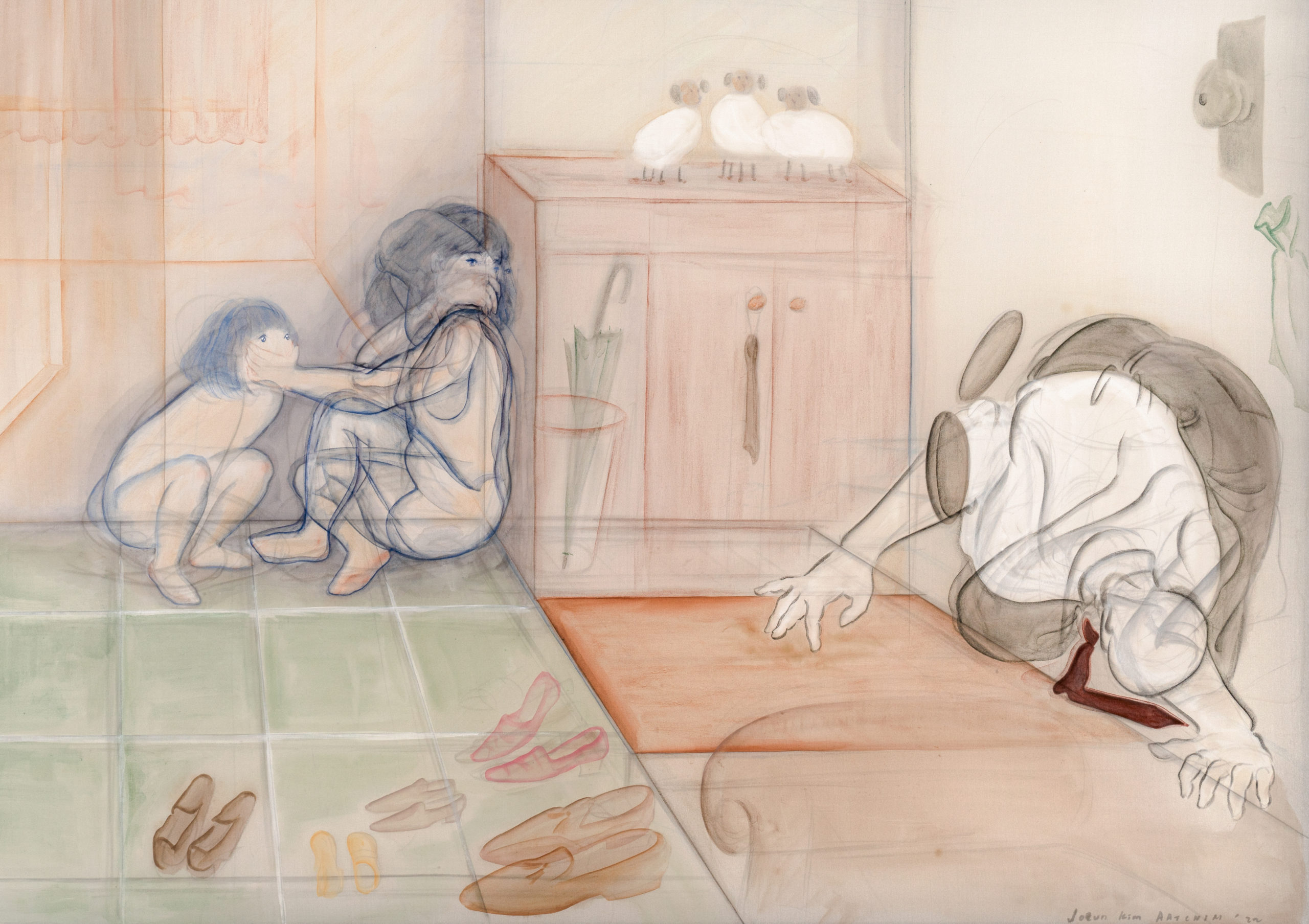

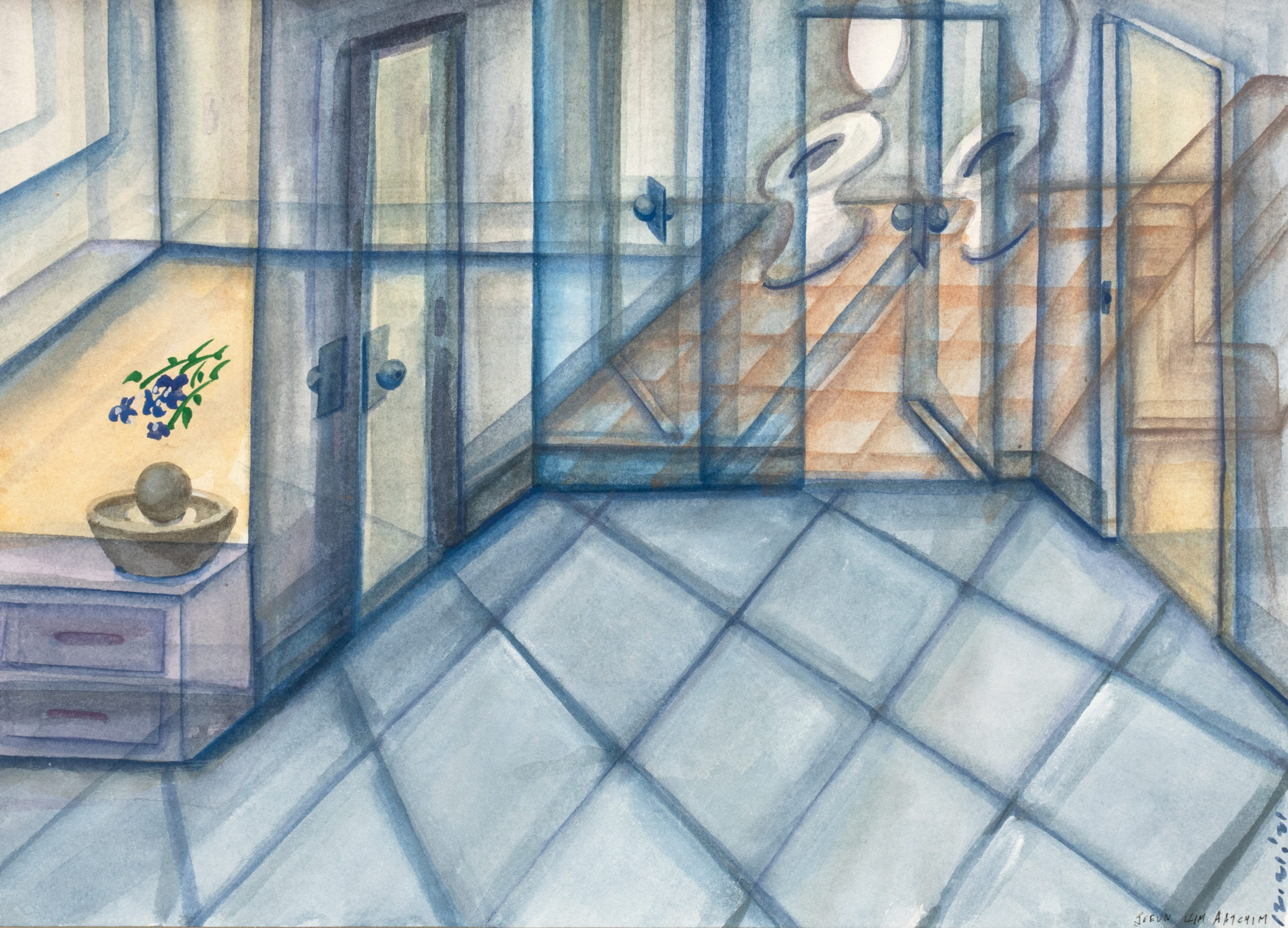

In 사자굴 [Sajagul—Then, out of the Den—her recent exhibition at Make Room in Los Angeles—Joeun Kim Aatchim created a series of drawings and paintings from her childhood memories: the family apartment in Seoul above a piano store, where she and her sister grew up and played—over a hundred times during their mother’s absence—a scene with a lion from the movie Jumanji (1995). These memories are not settled. It’s even a question whether these events happened at all. The strength of Aatchim’s work is to make you see something unreal, yet something that touches on feelings of both trauma and belonging.

Her technical skills are instrumental in creating this sense of invisibility and blur. She draws on silk with mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue. Sometimes she interposes multiple layers of silk, which give her paintings a deep sense of depth, almost as moving images in just one frame. A sound piece accompanied the exhibition which places the audience in a state of listening as well as viewing. We hear a piano playing. We see a lion roaming. And by reading the titles of the pieces on view, a narrative starts to build into an autofiction where the main character could be Aatchim herself.

The exhibition puts you into a delicate place where fantasy and dreams lead the dance. It’s not unpleasant, though hidden truths manage to surface. It creates a layer of weight on the airy canvas. Suddenly, the poetic enchantment morphs into a severe atmosphere. Aactchim’s art—beautiful and troubling to experience— questions universal concepts of birth, death, trauma, pain, and joy.

Over emails, the artist talks about her practice, the making of 사자굴 [Sajagul]—Then, out of the Den, and her love for books and drawings. — D.P.

사자굴 [Sajagul] — Then, out of the Den: An Autofiction in the Making

DOROTHÉE PERRET

Can you explain the meaning of the title of the exhibition and how you play with the Korean word A Saja—both as a language and a visual expression?

JOEUN KIM AATCHIM

The title was to conclude the painting series and the story because it is about survival, rescue, and how we’ve made it out of the Lions’ Den[WG1] . I paid attention to the differences in understanding the same word/world in children and adults, like a parallel universe happening in the same space: how children and adults comprehend the same word differently.

For instance, children would understand “사자 [Saja]—a lion, was roaming around the house,” as a scene with a fierce animal, like Jumanji. However, in the adult’s language (“newspaper” language) it means death and has many other meanings, such as the dead, the messenger of death, quadripartite, heir/heiress, and transcribing, with different combinations of Chinese characters, although their phonetic sounds remain the same, /sɑʝɑ/. I used those words as a guide to structure the scenes in the painting series.

Besides playing with multiple meanings, I have a word constellation in my mind for the Sajagul project, poetical fragments with their visual forms and pronunciations such as “then–den,” “paid off–pianoed off,” “debts–doubts,” “heard of–a herd of,” “hair– heir,” “rice–lice,” and “world–word.”

The pair Then and Den in the title is a good example of the mispronunciation of Th [θ] and d- /d/, sounds that Korean speakers have difficulty pronouncing their first time learning English. This mispronunciation is related to embarrassment, which is a frequent subject of emotion in my work because it symbolically represents one of the first human emotions—the shame and self-consciousness from the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. My previous solo exhibition title had the same pair of Th [θ] and d- /d/, Can Day See Me?

There are feelings of both accurate memories and ambiguous dreams that emanate from the work. How much of yourself do you put into the work and how much of it is just pure imagination?

My imagination is a by-product of my intense memory and urgent desire to see through everything. So I draw every viewpoint as if the object, figure, and spaces are see-through, which I find to be a form of intimacy. By intimacy, I mean that you can draw the sides you can’t see if you are familiar with the space, object, or person. Also, it’s a memory game: you can draw as much as you remember.

You are now based in New York, though the exhibition describes a place in Seoul where you lived during your childhood. There is an obvious geographical distance between the two cities that somehow echoes with the distance memory draws between the past and the present. Were you aware of these subtle intervals when you were creating the work in your studio?

I certainly was. The “intervals” are perhaps exactly where I stayed during the making of the project and in general. The time differences were more significant than the geological differences in a literal and metaphorical sense. I spoke Korean with my family to get as much information about the time to aid my memory. When I was back in my internet-less studio, it was just me in the memory palace, where time had stopped, and then when I showed the works and spoke about the results mainly in English, it was yet another significant shift in time. I have a piece in this show titled Still Life with Motion Sickness Crossing the Memory Palace, which was exactly how I felt about the intervals.

For a while I thought of a psychology study I read about time warps happening among bilinguals—about how bilingual speakers experience the passage, duration, and measure of time differently by the language. I can testify to that from my heartfelt experiences.

Transparent Material, Invisible Body

Can you talk about your technique of drawing on silk? Were you trained as a painter or a draftsperson? I believe you distinguish between the two practices.

I am truly a deep drawer more than a painter, I would say. I had always been a drawer, even before kindergarten, and had my first artist’s website when I was fourteen, where I shared my drawings and writings daily. As for formal training, I had four to five years of training in watercolor still life painting during my teenage years to prepare for the notorious university entrance exam in South Korea. The training was so intense that my watercolor pallet’s enamel scuffed off, and I had to replace the pallets every three to four months, but it sent me to a great university where I was a painting major for two years until I left for New York, where I haven’t painted for many years.

Yes, the distinction is clear to me, although it’s very subjective to each artist. I have established my own definition of drawing as well, which my bachelor’s degree thesis was about: how drawing is closer to sculpture or installation than painting. My definition of drawing is that if the line stands alone on a surface where it’s drawn—whether it’s drawn on paper, canvas, or linen or on a wall, floor, object, or someone’s skin—if the surface upon which it’s drawn remains visible, it’s a drawing if the line is not trapped by plane opacity around or behind it. The drawn marks and lines have their own movement agency and stand in and out of the space or surface. (Though this might be due to my stereoblindness!)

Drawings are never-ending stories, a perfect medium for essayists. A drawing is so humble yet never settling to compromise into a single narrative; it is forgiving and knows how to erase or cross itself to start over.

The transparency of the silk somehow almost erases all forms of bodily presence, as if the scenes you depict were only dreams. I’m amazed by your skills—how, by multiplying layers and movements, you somehow create a sense of emptiness. What comes into your mind while you’re drawing?

There are a few reasons my work has multiple layers/lines. First, my numerous accumulative trials to get the image right often remain visible in the drawings, which resemble the lines in my pure observational still-life drawings where I also have various lines around the object due to my eye misalignment.

In this Sajagul project, I used earth pigment (soils) to create the ground, so they became more painterly than my other works where lines float on the surface. Still, my desire to draw lies in my urgency to record; sometimes, when I have enough information in my lines, I am often satisfied without any colors or background, which aligns with East Asian paintings that include the void as part of the scene. However, even if I use mineral pigment like the East Asian tradition, the way I draw is quite unorthodox; I almost sweep and mop the pigments toward the outlines, so when you see my silk work’s shadow, only the line throws opaque shadows.

The way you double-layer the drawings in one frame manages to animate them like a storyboard for a long-form narrative. Are you interested in developing film or video work?

I have been obsessively experimenting with the depths in my works through various degrees of transparency by using different sizing methods and recipes—for example, to control how much can be seen through the layer behind. The movements and animated effect of the images are by-products, mimicking the way I see with my misaligned eyes or the way one’s memory sees.

I’ve been thinking of connecting my double-layered paintings to a new iteration of my ongoing video project called Your Poetry Reader (2014–ongoing), which has moving images with auto-generated voices with tempos that mimic classical poetry reading.

Because I work a lot with auditory elements, such as ventriloquist performance, voice actors, and audiovisuals, videos have been part of my project to support other still mediums. The double-layered paintings and my audiovisuals are rooted in the inspiration from my eyes: my need for reading voices that aid my dyslexic eyes and my stereoblindness.

About Books and the Café Anxiety Drawing Club

I’ve read that the exhibition also serves as a component of an artist’s book you will create. Can you talk about this project?

My writings in the space are to embody instead of to read, staging various audiovisual and tactile objects. Since 2016, I’ve drafted books in each exhibition installation as a physical editorial space, using a specific ticket-rack installation. I place an object like punctuation in the installation, stage images in a particular sequence, and shift the writing drafts around, just like editing a book in a physical space. Because the Sajagul project is installed a bit too far from where I live and work (New York City) to edit the draft on-site, I chose a video to show my work-in-progress draft and uploaded it to my website.

The book currently has six short bilingual essays in Korean and English. Also included will be my parents’ love letters from their college years in which they promised each other perseverance in any future hardship. My drawings and paintings in the Sajagul project can testify they indeed kept their promise in their most challenging time.

The editing is still in progress, but, fortunately, I met many good collaborators during the exhibition, so more contents are being added—hence the delay, though it’s all exciting. One exciting featured voice would be of the texture artist who worked on the lion in Jumanji, who happens to be my dearest friend’s mother. It’s too soon to reveal more yet, but I love how serendipity works in its magic and how it circles back to my ongoing topic of mother.

It’s not your first artist’s book. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but I think you’ve already created three of them: I will Bring You a Flower, I will Bring You a Vase (2014); Four of Mattresses Stacked on Misery (2017), and eye jailed eye (2019). What was your process when creating them?

You’re right; those are my artist’s books. I forgot to list Half an Eye (2012) on my website! And I just finished In Praise of Cry Breaks (2022), which I will launch this summer, with Korean, English, Chinese, and French translations. This book was an excerpt of Four of Mattresses Stacked on Misery (2017). Each book has a unique process, but what connects all of them is my intense desire to archive memories. So far, they have never been available for traditional means of purchase but have their own way of distribution.

Four of Mattresses Stacked on Misery (2017) is an anthology of iPhone memos from 2009 to 2017. Most of the artworks I made in this period are rooted in that book, so it’s a master plan. The text is formatted as a “forwarded message” in an email draft. The book is a mystery to me but certainly is a communication between me and my future self because I believe the sole purpose of the memo is as a favor to my future self—to help her recall. eye jailed eye (2019) is an anthology of words and lines. I drafted and edited it in a physical space during my solo exhibition with the same title.

Can you explain what the Café Anxiety Drawing Club is and if it’s still an ongoing project?

Café Anxiety Drawing Club Int’l is temporarily closed until further notice. This project was an entirely virtual international drawing club with participants from all over the world. I did this project in 2019, so it was ahead of its time, before the pandemic; now, virtual art meetings are more common. Perhaps in a physical space, I can dream of reopening when this pandemic passes and the word “anxiety” can sound fun again.

Although I teach drawing in the classroom and though other public programs, I believe that drawing is a personal business and should be done alone. But the sharing should be a together-activity! As I returned to intense drawing practice, I needed a safeguard—a group of my friends—artists to help one another stay afloat in a studio while maintaining a physical distance.

I loved my project and the artists who joined me so much that I turned the last weeks of the solo show into the drawing club’s exhibition in 2019. Also, because I was an Open Session fellow at the Drawing Center at the time, I had the chance to show the project as a public program, inviting general audiences to Café Anxiety through generous support by the Foundation for the Contemporary Arts and Rosario Güiraldes, and by Lisa Sigal, who invited me to organize the program. I will be sure to let people know when Café Anxiety is open and serving our wildest imaginations again!

Text © PARIS LA.

Jeoun Kim Aatchim,사자굴 [Sajagul—Then, out of the Den, Make Room, Los Angeles, April 16–June 4, 2022, from top: Alone After the Shout, 2022, earth and mineral pigment watercolor, casein, wax, resin on linen; Still life with An Alone time, A Candy Bar, an Ember Cup, and Poet’s Daffodil, Over Mother’s Poem (Item Found in Her Pocket by a Child Detective), 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue on silk, ink on cotton; Exodus Us— by the Name of Double Edge Roses. Deliver Us— from the Herd of Roaring Pianos. Man Does Not Live by Sack of Rice Alone, Item Repelled. Game Over, 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, refined pine soot ink, charcoal, graphite, chalk on silk; A Safe Coffin—A Tale of a Tail, Out of the Blue (Kinderszenen), 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, refined pine soot ink, charcoal, graphite, chalk on silk; Deliver her—Like a Thief in the Night. We Heard of Lions, Above a Herd of Pianos, 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, refined pine soot ink, indigo dye, charcoal, graphite, chalk, whitegold leaf on silk; Doubt The Hands (The Debt Collector Seeks the Father Through a Milk Delivery Hole), 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, refined pine soot ink, charcoal, graphite, chalk on silk; Receive-Her, but No Answer. Father’s Winter Hardy Camellia Tree, an Overdue Videotape, Unlocked Bedroom, the Light of Blessing, and the Fin, 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, refined pine soot ink, charcoal, graphite, pastel, chalk on silk; Still life with Motion Sickness crossing the Memory Palace (Still life with Jumanji, Hansan Mosi, Brass Pedals, the Ani-mal Crackers, and Yellow Roses over the Failed Attempt of Portraying the Marble Floor Apartment), 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, colored pencil, charcoal, chalk on silk, casein on canvas; And My Wishes—I Wish I Had Told Him That He Did What He Had to Do for Her and the Girls, 2022, earth and mineral pigment watercolor, casein, resin, wax on linen; Draft for the Book 사자굴Sajagul, 2022 (detail), installation with glazed porcelain fingers, brass piano pedals, VHS video, and CRT monitor, video with color and sound with expanding length in a loop; The Apartment with Marble Floor Above a Used Piano Store. The First Recall Attempt While a Tumor being Removed from my Mother’s Spine, 2022, casein color on paper; The Untouched and the Delivered—A Tale of a Moon Light Prayer in the Lions’ Den, 2022 (detail), mineral and earth pigment suspended in glue, whitegold leaf, refined pine soot ink, charcoal, graphite, chalk on silk. Images © Joeun Kim Aatchim, courtesy of the artist and Make Room.