THE GREAT SOMEONE

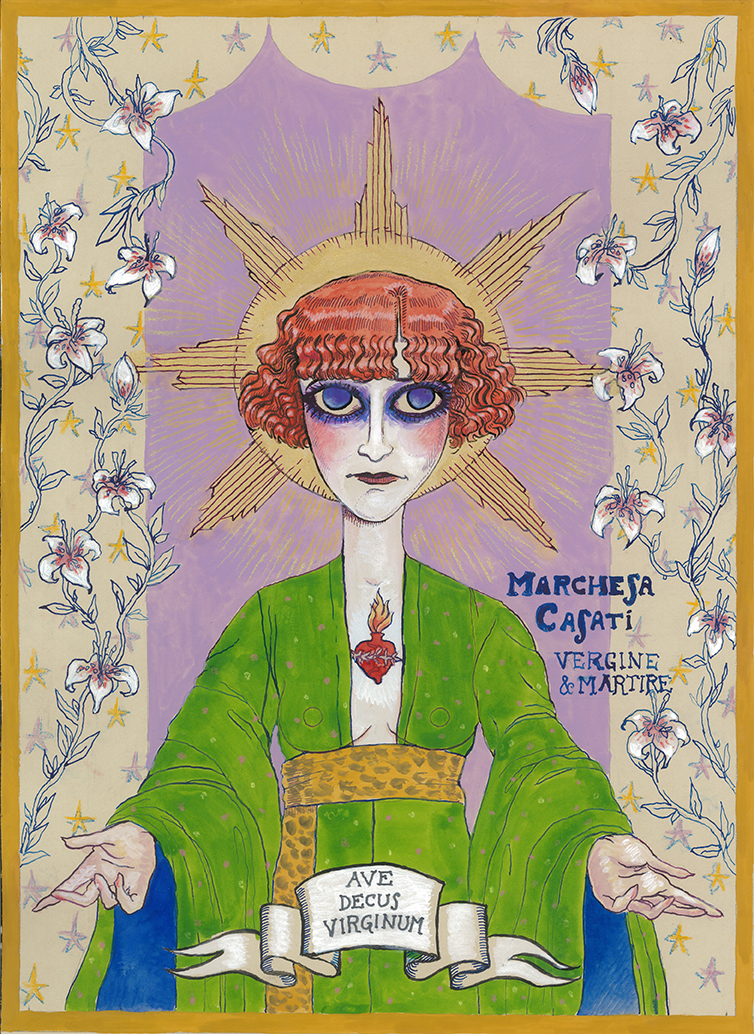

Essay and artwork by Massimiliano Mocchia di Coggiola

Beware of the dandy. He has a cold heart and a cold hand, like the iceberg that sank the Titanic. He could kill to have his necktie on right.

Jean Cocteau, the French poet-of-all-trades, had his character Orpheus say: “My friends, pretend that you’re crying for I’m pretending to die.” Cocteau himself feigned a disappearing act in 1963, and dandyism has continued to exist ever since—despite May 1968, despite the horrors of the 1980s and the mainstream fashion of the 1990s. And now in the new millennium, dandyism is doing just fine.

In his embrace of a modus vivendi without creed that adheres to no school, neither altering history nor inciting veritable revolutions—not even in clothing—the dandy thrives. The only climax in this story—if one wishes to take the trouble to tell it—is that the original dandy actually exists, recognized as such by Barbey d’Aurevilly, Baudelaire, and other more intellectual dandies: George Bryan Brummell (1778-1840), otherwise known as the Beau. He has left nearly nothing in writing (other than letters, and a book about the clothing of the ancients—though there are some doubts about the authorship of the latter). He never bothered to save a painted canvas or a sketchbook for posterity. He was an artist in his own right, nonetheless—designer of a collaged decorative screen, now lost, and draftsman of a small pencil drawing depicting a cupid with a splintered appurtenance, punningly titled The Broken Bow (beau). Brummell was exactly that—a dandy who applied himself more to drawing and painting his life rather than dreaming up innovative ideas for the benefit of humanity.

Dandyism originated at a time when the long-standing values of birth and wealth were being challenged. The revolutionary upheavals of the late eighteenth century, which had officially quashed aristocratic mythos and models, gave men who enjoyed distinction and fancy dress one sole reason for adopting it: style.

Every dandy seeks to embody his own definition of the term, creating his own look and—in principle—keeping his distance from any causes or cliques. A true dandy never calls himself a “dandy,” since he has already gone to great lengths to be one. Only Brummell dared pronounce the word when asked if he was an aristocrat, a snob, or goodness knows what else. But Brummell was the first. Somebody had to own it!

Circumscribing the dandy is far from simple. Barbey d’Aurevilly wrote in his treatise on dandyism that it was easier to define a dandy by what he isn’t than what he is. Still, it is worth a try to venture a definition by reviewing the key timeless characteristics of the dandy.

- Formal elegance: This is both at the core and on the surface of the dandy’s identity. The dandy cultivates an extreme form of elegance with the same vigor that mountain climbers or enthusiasts of vegan restaurants cultivate their obsessions. The dandy’s elegance must be classic and a tad outmoded, with little or no acknowledgment of modernity. Fashion only concerns the dandy tangentially, as if by chance. Another dimension of his elegance is understated eccentricity. No two ways about it, his impeccably meticulous attire will always stand out whether in 1808 or 2018.

- Wit: Being a dandy also entails mastering the art of conversation—the right word, repartee, the last jab. Oscar Wilde’s aphorisms are a perfect example.

- Nonconformity: Refusing orders and rejecting dogmas and rules imposed by others as well as societal laws, the dandy stands behind a singular conception of aristocracy that may combine with odd, sometimes wacky political ideas—or, conversely, a total rejection of the world and its Disregarding rules goes hand in hand with an astute understanding of them since the dandy likes to master things before opting to go against them. Is this linked to a certain sense of superiority? Does the dandy consider himself to be entitled?

- A je ne sais quoi: Like the concept in the song by Yvette Guilbert, the dandy is one of those beings that becomes surreal or supernatural whenever one tries to put his charm into words. The basis of that charm is not only the three preceding points but also a certain something that defies definition. Is it the nil mirari dear to Baudelaire and the Stoics? Or the mortal boredom lyricized by Gainsbourg (who was not a dandy in the least)? Every dandy is unique; they are all so different from one another that it can sometimes be hard to fit them together into a coherent group. Yet it is their difference that is so appealing without being able to put a finger on why.

It was thus Brummell and his followers who originated the modern dandy, a superficially perfect creature, solely preoccupied with celebrating a liturgy of taste. The dandy of yore, like today’s, must distance himself from anything that might mar his immaculate appearance: passions, morals, political and professional ambitions. The dandy would be a hero that—at center stage—has no need whatsoever to prove his heroism and who actually manages to live without doing anything in particular.

The nineteenth-century dandy was destined to become, by turns, an aesthete thanks to Wilde, a poet on account of Cocteau, or a Baudelarian art lover. During the twentieth century, with the rise of ideals such as equality, responsibility, and the expenditure of energy for the community, dandies continued to perpetuate their ideals of superiority, irresponsibility, and passivity: “Being a useful man has always seemed to me to be something truly hideous!”1 Whether they are adulated or detested, photographed or denigrated, dandies continue to inhabit the world. It’s tough being a work of art.

Dandyism is therefore not dead as some may like to believe. It is more alive than ever. Since coming back into fashion, the term dandy only reads through appearance, clothes, and habits, having been emptied—in theory and in person—of all semiological value. Today, the figure of the dandy tends to be seen as a vain being, an affected fop, reviving the same pejorative sense it had assumed in the nineteenth century. However, are his excesses the true expression of dandyism? Do his ticks faithfully reflect the spirit of those men who sought to affirm their singularity?

Ever since the origins of the movement, dandyism has raised questions whenever it reflects a different way of life, in which appearance is profound and extremely contagious rather than frivolous. This is when it strives for a radical sophistication, a new nobility of soul. The bourgeoisie having won its bet against the aristocratic spirit, mainstream fashion having efficiently erased the idea that clothes are also a form of self-expression, the 1990s delivered us a lucrative, uniform, low-end aesthetic, whose side effect was to prevent any metaphysical or social revolt. If it follows that men also construct their sense of self through what they possess, the individual, mired in rampant consumerism, has lost the desire to own beautiful, solid, durable and unique objects—and thus a soul. The contemporary dandy has again become a revolutionary through his mere existence. Imposing his contempt for trends on the world, standing out for his sartorial independence (the tip of the iceberg of his philosophy of life) and his search for beauty at any cost, the dandy constitutes a reaction against the misleading idea on which the whole of current society is based: that indispensable modernity amounts to ugliness, neglect, uniformity. The violation of beauty began when we were led to believe that beauty was merely an effect of fashion. And yet, “What deserves our recognition? That which is the most dignified, that which is the truest? No. That which is the greatest? Sometimes. That which is the most beautiful? Always.”2

When everything is formatted, packaged, wrapped, labeled, and delivered, it is hard for us to understand a person who has the ability to stand out from the crowd. Specific and reassuring codes of behavior govern how we identify with a group or develop a social identity. The dandy is familiar with these codes and knows how to flout them, adopting the appearance of a respectable person without, however, acting like one. At ease everywhere, he nevertheless avoids belonging to any socially recognized category. Eschewing prejudices and preconceived ideas, the dandy constitutes a caste unto himself, which may be why he often finds himself both loved and hated in the world, especially by the bourgeoisie. For he is truly anti-bourgeois while feigning to pass for one of them (with his suit and tie!), undermining the system from within.

Can a dandy be a woman? It has recently become so problematic to discuss gender without ruffling any feathers that political correctness is required under any and all circumstances. Would a woman then be “a dandy like another”?3 Not necessarily. Attempting to argue that a woman can be a dandy would be like saying that a woman can also have prostrate cancer. Words and their history carry more weight than feminist revisionism: the dandy is male and couldn’t care less about such matters. On the other hand, there are so many other words to describe a female dandy—dandizette and quaintrelle being the most relevant—that it’s a wonder nobody has so far tried to reintroduce them in essays. It is hard to determine which women have been female dandies. Recent efforts in this area have been less than satisfactory. As for myself, I am convinced that an original dandizette exists: the Marquise Luisa Casati (1881–1957), an absolute paradigm of what any women who deems herself a dandy should admire. With her unrivaled lifestyle, her generosity, her taste for scandal and extravagant dress, she was a merveilleuse who immersed herself in luxury to a degree that even the wealthy of today could not fathom. She left nothing in writing. Just like her male counterparts, her true work of art was her life, no less!

This essay was originally published in PARIS LA 16, the “Fashion and Writing” issue (2018–2019).

Text © PARIS LA.

Notes:

1. Charles Baudelaire, My Heart Laid Bare, 1887.

2. Eugène Fromentin, The Masters of Past Time, 1876.

3. Alister, La femme est un dandy comme les autres, (Paris: Pauvert, 2018).

Images, from top: Massimiliano Mochia di Coggiola, Beau Brummell, ora pro nobis, 2017, mixed media; Massimiliano Mochia di Coggiola, Marchesa Casati, ave decus virginum, 2018, mixed media.

Links to the blog of Massimiliano di Coggiola www.mmdc-art.com and to his fashion brand www.mocchiadicoggiola.com